The Fires This Time

“You should come over… no you should come over… but I have water pipes… but California always burns… every part of California burns.” – overheard at my gym, 01/10/25

“Each new conflagration would be punctually followed by reconstruction on a larger and even more exclusive scale as landuse regulations and sometimes even fire code were relaxed to accommodate fire ‘victims’. As a result, renters and modest homeowners were displaced from areas like Broad Beach, Paradise Cove, and Point Dume by wealthy pyrophiles encouraged by artificially cheap fire insurance, socialized disaster relief, and an expansive public commitment to ‘defend Malibu.'” – Mike Davis, “The Case For Letting Malibu Burn ” (1998)

I write this as Los Angeles finally stops burning, following three weeks of arguably the greatest conflagration in California’s history. LA faces dozens of deaths, incomprehensible damage, and permanent life changes for tens of thousands of residents. I personally know many people who lost homes or livelihoods, who are hosting family and friends who did, or who are barely returning after evacuation orders. Yet the events feel surreal and disassociating– possibly because it’s impossible to fathom such loss, possibly because while this is the worst yet, it’s both a bizarre pantomime of what came before and a harbinger of even worse to come.

The most disturbing thing is that this was highly preventable and predicted by many commentators over many years. Decades of research and the occasional galvanizing catastrophe have driven recommendations for development reforms, controlled burns, modernized buildings and scaled fire services. Yet incidents have grown significantly worse while yielding little meaningful action from decision makers. The best policy changes have amounted to rescheduling the crisis. The worst have only hastened it. We’re seeing such behavior right now, with government at all levels loosening restrictions to spur rapid, unfettered private development.

Still, the current conflagrations might finally drive meaningful transformation, given their winter timing, geographic and economic spread, and obvious connections to austerity, privatization and climate change. But this will only occur if rooted in an organized, working class movement that understands the economic and political forces creating the fires, articulates bold, immediate policy demands, and mobilizes a base among the displaced, Angelinos in general, and even communities absorbing the coming wave of LA climate refugees. Such a movement also requires understanding history in order to change the future.

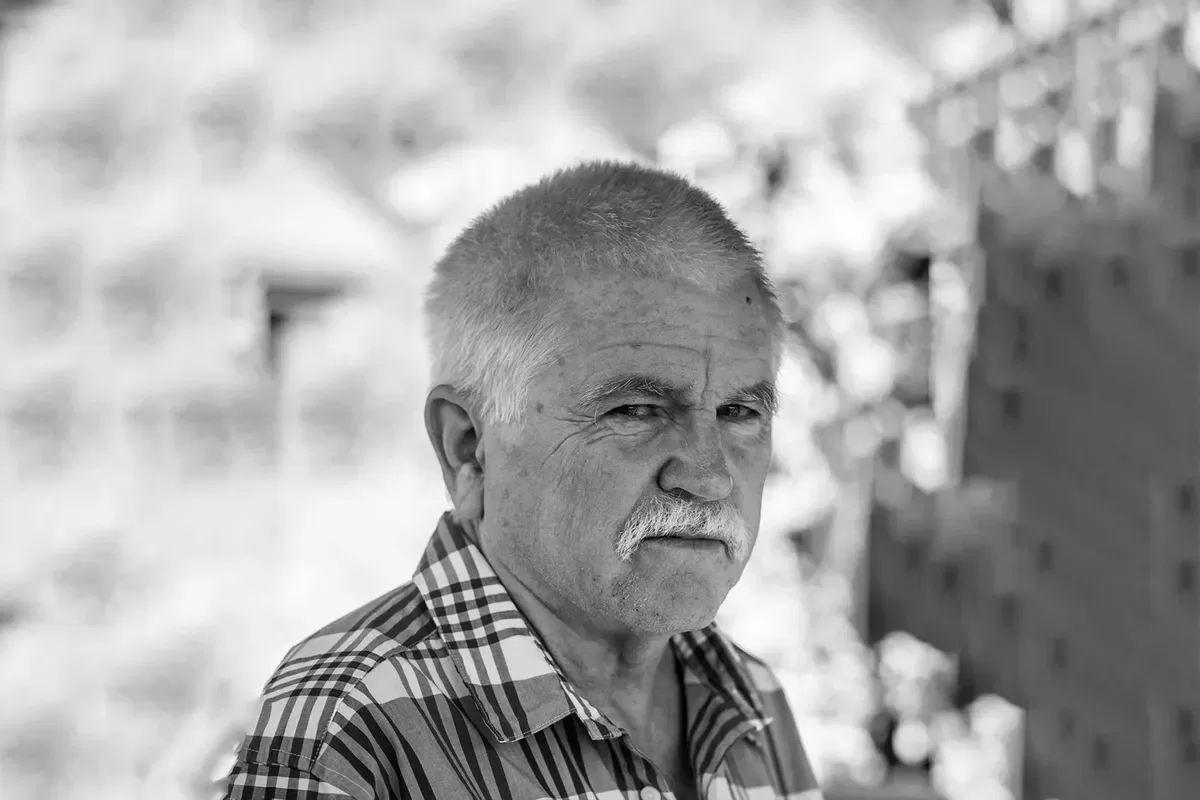

Luckily, we don’t have to turn far for guidance. The most prescient and eerily accurate predictions of Los Angeles burning –and what to do about it– come from two of my personal favorite writer-activists, Mike Davis and Octavia E. Butler. Both wrote about LA wildfires over 25 years ago, but their visceral accuracy, reading of history, and deep dedication to their community resonate now more than ever ever. They remind us that while crisis under Capitalism is inherently cyclical, we are enduring a particularly potent crisis moment. What would they think of the fires this time?

Mike Davis just before his passing in 2022.

(Image credit: NPR obituary)

Octavia Butler

(Image credit: Beacon Publishing)

Davis and Butler astutely analyzed historical conditions to warn us about the future– Davis via working class social history and Marxist Geography, Butler through intersectional science fiction forecasting dystopias and social movements. They share deep critiques of racism, xenophobia, and the many interwoven oppressions under Capitalism. More importantly, they share a sense of hope that everyday people of all backgrounds can confront and shift power, even when all systems are stacked against them or cycles of domination lead to disempowerment and even forgetting. They most intersect in their offerings of accessible, compassionate, inspiring narratives.

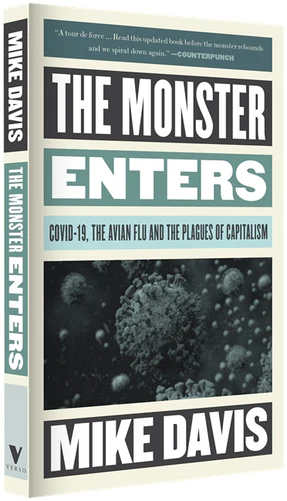

Davis’ prolific social histories covered many topics, but he wrote most beautifully about race, class and the environment in Los Angeles and California. His early works, “Prisoners of the American Dream” and “City of Quartz” received major recognition far beyond the left, and he earned newfound popularity in recent years for his work connecting Capitalist development to pandemics (2005’s Monsters at our Door) and broader social crises, both real and imagined (1998’s Ecology of Fear).

Davis wrote a follow-up to to “Monster” in 2022, focusing on the COVID pandemic. “Ecology” includes his long-form, brilliant essay, “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,“ which resurfaced in the popular consciousness after LA’s 2020 and 2021 fires and garnered him extensive interviews before he passed in 2022. His insights into these areas and many others only grow more poignant with time.

In the essay, Davis reviews a century of development, zoning and fire code in Los Angeles, counterposing Malibu’s canyons and beaches against Westlake and other downtown LA neighborhoods that spent most of the 20th century as slums. He weaves together the institutions and key players behind decades of neglect for LA’s working class residents, for Malibu renters and limited means homeowners, and for the environment. The system was always arranged to benefit wealth consolidation, predatory development, and extractive rents or fire insurance. Beneath all is a constant neglect of root causes, whether from the invasive chaparral becoming tinder after a century of controlled burn bans, the relaxing of construction requirements after each Malibu fire, or repeatedly abandoning code enforcement in poor neighborhoods.

There’s no way to give such a nuanced analysis its due, particularly when Davis braids historical data and narrative with his own love of the natural environment, or recounts the passionate efforts of working folks and left politicians to create reform in downtown LA. So please read the Ecology of Fear. I’m focusing on a few of Davis’ core points elucidate how bad things already were in 1998, how they’ve only compounded since then and -crucially- how contributing factors such as cheap, widely available fire insurance have suddenly and violently disappeared in recent years. These grim realities highlight that major events such as fire are themselves dependent on political conjunctures, and the obvious, essential need for a new system.

Davis tracked 1,636 homes that had been destroyed by Malibu-area wildfires between 1930-1996. He noted that the risk factors seemed to be increasing over those years, and predicted that this would only get worse. He was- of course– correct. Large fires have since become less frequent but far more dangerous. According to CalFire, the 20 largest fires in state history have all occurred since the year 2000. LA and Ventura County’s 2018 Woolsey fire burned 1,643 structures, or an excess of the homes burned in the 66 years prior to Davis writing. The number of structures burned in the first two days of the combined January 2025 fires already far exceeded these numbers, with well over 18,000 structures destroyed some three weeks in.

For Davis, the responses to any given fire are both emblematic of problems with the system and contribute to worsening the next crisis. In an almost poetic tone, he decries “each new conflagration would be punctually followed by reconstruction on a larger and even more exclusive scale as land use regulations and sometimes even fire code were relaxed to accommodate fire ‘victims.’ As a result, renters and modest homeowners were displaced from areas like Broad Beach, Paradise Cove, and Point Dume by wealthy pyrophiles encouraged by artificially cheap fire insurance, socialized disaster relief, and an expansive public commitment to ‘defend Malibu.'” The response is the problem, while the rhetoric -almost an ideology in and of itself- obfuscates responsibility.

There is one significant change that must be confronted directly. Davis was right in 1998 to note the lure of “artificially cheap fire insurance.” But, in an unsurprising twist, the same industry greed that fueled home building in floodplains, coastal areas and fire zones across the country has finally dried up, become inundated with insolvency, or totally burnt out. Reports are claiming already $4 billion in insurance payouts from the fires, and up to $250 billion in losses coming. While I don’t have the data, I guarantee that a significant portion of structures -most likely those in the lower income tiers for these neighborhoods– were either uninsured or underinsured. People living in them lost everything and face little to no recompense. Some of the over-leveraged and underinsured wealthier folks are broke now, too. If allowed to fester long enough, disasters and crises are proletarianizing.

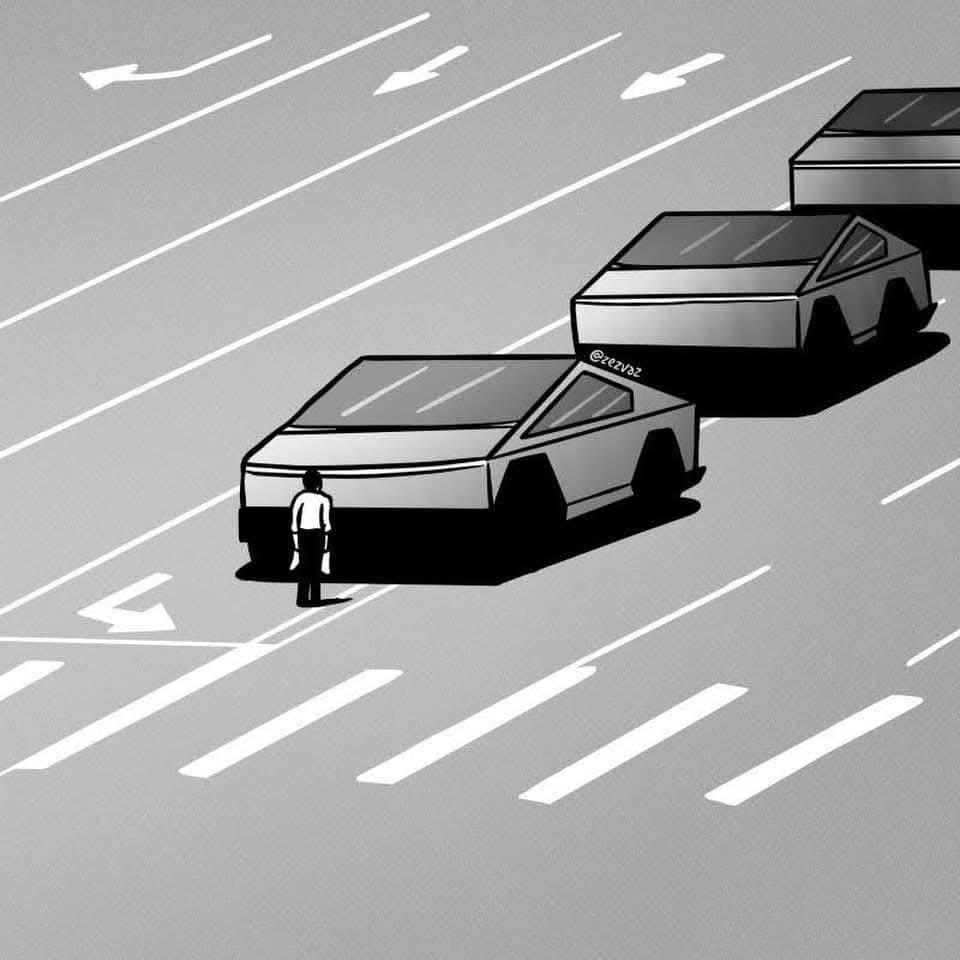

These words all still ring true, and have only been amplified by the growth of disaster Capitalism over the last few decades. We’ve all seen the social media posts about water supplies diverted for private use, LA fire maps hidden behind paywalls, mega rich tax dodgers offering a fortune for private fire services, or property management companies inflating rental listings, sometimes while the prospective new tenants were already there with an offer. This is just the tip of the iceberg. And yet the press emphasizes the (in my opinion shockingly minimal) number of arrests for petty looters, the fear mongering around vagrants causing fires, and what Davis aptly calls the “Incendiary Other.”

Of course, there have been many changes in the political economy of fire since Davis’ polemic. Water privatization has accelerated dramatically. Development is even more unfettered. Austerity budgets have undermined fire and social services, even as policing, stadium construction and developer incentives expanded. Chaparral and suburbs still sprawl. There are more power lines and homeless encampments waiting to accidentally burn down a whole neighborhood. Public, private and volunteer fire services around the Western US are bravely sending overworked rigs and firefighters to help battle blazes. You could say that something of this magnitude was overdetermined. And, yet, many social media feeds are talking about how LA spends an exorbitant amount to fight homelessness and almost nothing on fire.

Image credits: Associated Press

Whole neighborhoods face a fraught future. The few mobile home parks in Malibu were likely speculative investments with minimal thought given to current residents. Parts of the totally burned middle class Black neighborhoods in Altadena appear to have been underinsured.

The folks living in mobile homes will get almost nothing, whereas the speculators will be able to cash in and build up with minimal costs. The demographics of Altadena, itself a regionally desirable area, will likely irrevocably change as homeowners of color are displaced into Riverside or Ontario counties, or out of the region entirely. Many are already homeless and some are still missing… even as the families with financial means or remote work get out of California entirely.

Queue the woman from my community center gym last week, who appeared to be a recent, working class immigrant from Africa or the Caribbean. Her passionate call admonishing people to get out of California revealed the regional magnitude of a crisis hitting LA. It reminded me that climate migration is already unfolding, and not just from the global South to the United States. More than anything, it reminded me of the revolutionary, Black, queer science fiction author Octavia Butler, who centered dystopia-driven diasporas in major works such as Lilith’s Brood, Kindred, Seed to Harvest and, most notably, Earthseed. While Butler spent much of her life in Seattle, she sets large parts of her work in Southern California, focusing on characters living in or trying to escape LA neighborhoods that have now burned.

Butler’s “Earthseed” duology is widely considered among the most visionary science fiction series of the last several decades. It goes deep into economic and racial inequity, critiques of Capitalism and religion, and has inspired organizing models based in empathy, mutual aid networks, and even a beautiful black-owned bookstore here in Tacoma, Parable, that unfortunately just closed. For a sampling of her influence, see the works of Adrien Marie Brown, and specifically her reflections on activism in “Emergent Strategy” or her compilation of activist-penned radical science fiction, “Octavia’s Brood.” I don’t share all of Brown’s views (she’s a bit too woo-woo for my practical, socialist orientation), but I share her love for organizing and Octavia Butler.

The first Earthseed book, “Parable of the Sower” begins in a gated LA suburb in late 2024, with tragic events -including wildfires- driving protagonist Lauren Oya Olamina to flee California for Oregon as she develops her empathy and mutuality-based religion, Earthseed. Throughout, she confronts inequality-driven violence, widespread despair and rising national Christo-Fascism. The climate is an ever present, ever-changing force, leading to Lauren’s belief that “God is Change.”

Lauren expands her philosophy and spiritual/political base in “Parable of the Talent,” confronting a delusional, messianic President whose slogan is “Make America Great Again.” It might as well be a historiography of climate migration under Trumpism. And, while it is ultimately fiction, there is clearly much to glean for the present moment.

Octavia Butler’s Earthseed Duology

(Image Credit: Google Books)

Internal US climate migration has been a force for many years, and I’ve met numerous self described US climate refugees in the Northwest. But what has until now been a slow trickle is about to become a flood, particularly from Los Angeles, the Southern California inland empire, and the broader Southwest. I hate borders and want to welcome everyone with open arms. But I pause knowing the people at the front of the line can afford to pick up and move… Older, wealthier, whiter, more able-bodied people. This will undermine their home economies and tax bases, and wreak havoc on Oregon and Washington housing markets. It certainly ain’t a new intergenerational, interracial spirituality based on mutualism and loving the earth.

Back in December, I stumbled upon some memes referencing “A Few Rules for Predicting the Future,” an Octavia Butler piece from Essence Magazine back in 2000. In it, Butler references conversations with students asking her about predicting the future. She says “All I did was look around at the problems we’re neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters.” When asked for an answer, she says “there’s no single answer that will solve all of our future problems. There’s no magic bullet. Instead there are thousands of answers–at least. You can be one of them if you choose to be.” While they may sound like aphorisms, I see her words are powerful and inspiring guideposts for action. Yet the Eaton fire almost burned the Altadena cemetery housing her grave. So… Make Octavia Speculative Fiction Again?

Mike Davis was also prescient in an ironic, literary sense. In the essay, he mocks press fixations on prominent celebrities who lost their homes in 1990s fires, and others who helped them. He recounts how Anthony Hopkins offered Dick Van Dyke a free apartment stay on his property after Van Dyke’s house burned down. How would Davis feel seeing press coverage of Hopkins’ own house burning down last week, along with Billy Crystal’s and the Pasadena Synagogue? How would he respond to the scant mention of apartment buildings, trailer parks and several mosques that burned? Davis skewered the press of his time for covering celebrity homes over tenements. This time he would skewer them for renters, workplaces and entire faith groups.

But would Davis really want to “let Malibu burn?” I doubt it, at least not in the sense that some of the environmental or anarchist left fetishize. Yes, Davis thought it was madness to overdevelop, not learn from 100+ years of mistakes, or even to have settled such a dry and inhospitable place. But this was a mixture of rhetorical flair and practical solutions (such as controlled burns). Davis was committed to everyday people -particularly in his longtime home of LA– and opposed to solutions that harm the working class. He and Butler would both see this pseudo-left take as abandoning community responsibility and seeding grounds to the worst elements– the libertarian, anarcho-capitalist ideologies and ideologues rising in legitimacy everywhere. The type that gobble up land and young minds.

So, what is to be done? The obvious answer is also the seemingly unattainable one. We need to move away from sprawl-like, individualized and increasingly uninsurable private development in firezones and instead push for public housing, public parks, and public luxury. The municipalities and the state should intervene, use emergency powers and eminent domain, and begin a process to decommodify as much of the affected land as possible. This needs to start with identifying safe, free transitional shelter for those who need it, then halting the various “fire sales” and other predation already underway, possibly through creating a land bank that can compensate non-corporate homeowners for losses and hold property in common.

After that, yes, Los Angeles should rebuild in these areas. But instead of the development madness of the last century, there needs to be an emphasis on safe, affordable, accessible density. This means public and social housing. It means cooperative apartment buildings and rent stabilization. It means an adequate, guaranteed emergency water supply. It means roads wide enough to accommodate emergency vehicles, and that ideally are overwhelmingly used by mass transit the rest of the time. And it absolutely must mean easy access to beaches, foothills and parks that all Angelinos and Californians deserve, but Davis notes some have never seen. This tragic loss can turn from a crucible into a parable, one that drives real innovation at scale in LA and far beyond.

None of this will happen without concerted, resourced organizing, which likely feels like a tall order amidst such broad devastation and the re-ascendancy of Trumpism. But there are certainly opportunities, particularly among those displaced and looking for housing or support. From cursory research, it looks like folks are starting to self organize, form mutual aid groups and connect with community organizations. But people need to put immense pressure on the city and county of Los Angeles for specific policy changes and investments (both immediate support and long term infrastructure). This must be connected with economic action directed at landlords, property management companies, banks and developers. The fact that this is deeply and widely felt by “middle class” homeowners with skin in the game (rather than just celebrities and the working poor) increases the chances for a longer-run, successful movement.

The most effective route would combine traditional models coming out of the labor and poor people’s movements (such as rent strikes or occupying vacant buildings) and environmental direct action approaches at the site of development (such as blocking demolition or construction) until the jurisdiction agrees to basic demands. There is real economic and political power at play, meaning there’s also real opportunity for coordinated action. Billions of dollars of loss and resources are on the table, whether via unpaid and unpayable insurance claims, huge tracts of developable land, or major municipal, state and federal grants. More importantly, there is a bonus army of displaced people with possibly the most meaningful and widely understood grievances in LA history. Yes, this is doable even under Trump. I’m hopeful that the LA Democratic Socialists of America chapter takes a major lead.

If Mike Davis was here, he’d obviously admonish us to stop fearing using fire as a means to control underbrush such as chaparral, push for controlled burns and fire funding, to allow the return of other native plants, and to think of people as in communities, rather than investors or insurance plans. And, after her 500th “I told you so,” Octavia Butler would encourage us to use radical imagination whenever possible. She’d push for bold, visionary change based on an empathetic understanding of community and what constitutes “us.” I like to believe both of them would support all of these policies and much more. Beyond anything else, and maybe after a little sad laughter, both would remind us that these conditions were created by systems of domination, and the only way to mitigate them in the future is to organize to tear those systems down.