The Acid and Electro Revival, Black Joy and Working Class Resistance

I was recently messaging with Jack Coleman, a producer and DJ from Portland, Oregon, about his D.Vices Made of Stardust EP. His two electro bangers and a remix by Dibu-Z blew up the Beatport charts for months. I shared that I loved all three and was rinsing them on repeat, closing sets and parties with their melodic grittiness. Jack expressed surprise that he’d pivoted into uptempo electro (136 Beats Per Minute), that folks loved the speed, and that these sounds were all the rage again. I had similar observations over a couple years of DJ streams, music charts, and infrequent COVID gatherings. What was an emerging trend accelerated dramatically during the pandemic. The same is true for acid house of any tempo, but particularly slow, dark, international acid disco.

D.Vices “Made of Stardust” EP. Out last year on most digital music download sites.

Click here for Soundcloud or image for Beatport.

My hunch is that this divergence from the exceedingly formulaic world of dance music is because electro, acid and the harder sides of techno are inherently gritty, unpolished sounds. They express a tension and angst that feels more appropriate to the current moment than -let’s say- sleeker techno, overproduced deep house or bouncy tech house. Moreover, whether contemporary folks realize it or not, they were originally all working class forms that emerged in a de-industrializing, tumultuous period and were produced with cheap, limited tools that forced adaptation and boundary-pushing. The same innovation permeated their expressive 1980s fan cultures that survived for decades and appear resurgent today. All were reactions to political incoherence, the promise of prosperity with none delivered, “urban decay” and the rise of neoliberalism. Uncertain moments with growing inequality often lead to such explosions.

Styles always come back around. But why?

While we shouldn’t romanticize how inequality drives art, it’s also OK to celebrate joy as an act of resistance, particularly when it creates expressive, timeless and -in the case of acid- trippy as fuck music. Maybe that’s why perpetually narrow-tasted ravers of all stripes admit to liking both acid and electro. Critics have long noted this, too, including seminal rave culture websites such as Ishkur’s Guide to Electronic Music. Ishkur described the sonic and technological origins of different styles, with example tracks and commentary on each. It’s still around (several iterations later), although less snarky than in its early years. Ishkur unequivocally called 303-tinged “Chemical Breaks” the best genre of electronic music, citing the timeless sense of being at the underground rave whenever listening. I was inclined to agree. I’m not gonna die on that hill these days, but the claim holds up. Urgent music born of resistance is often timeless.

Taste is subjective and forms come in and out of vogue. The current revival will end sooner or later and already faces sonic regression to the mean. Sometimes cycles shift due to changing tastes, sometimes from new tools producing fresher sounds, and frequently because people can only tolerate so much convergence around an increasingly algorithmic center before listlessness sets in. Regression is inevitable under Capitalism, where tragically internalized profit motives destroy meaningful expression. It’s true even with already formulaic dance music, where fans hear infinite space for experimentation and non-fans hear mindless drudgery. But I believe the stylistic and economic undercurrents of acid and electro mean they don’t give a fuck, just as with conscious hip hop, Drum & Bass, grittier styles of rock and similar angsty sounds. They cycle in and out in response to market forces, but not those of consumer demand. They originated as joyful resistance. They re-emerge in periods of economic and social tension.

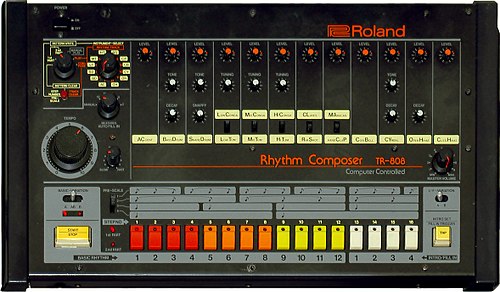

Images of a 303, 808 and 909, from top to bottom. Taken from Wikipedia

The cultural and economic roots of good times

The roots of electro, house, acid and techno all stem from the same few instruments applied in different yet concurrent contexts and are the subject of much legend and lore. One simplified origin story is that in the early 1980s, Roland released a series of machines intended to accompany musicians desiring a rhythm section. The TR-808 and 909 were drum machines with banks of synthesized sounds emulating percussion instruments. The TB-303 was a bassline emulator with filter, resonance and envelope controls marketed to accompany guitar players. Crucially, both were sequenced in configurations of simple, 16-beat patterns. The only problem was that live musicians thought they sounded cheesy and barely resembled the instruments they sought to copy. Meanwhile, competitors launched drum machines featuring actual recordings, along with a host of programmable samplers. They were only on the market a couple years. The 808 and 909 sold relatively well, but the 303 almost faded into obscurity.

That was until young Black men in Chicago, Detroit and New York started tinkering. In Chicago, it was via a racially mixed, queer-friendly disco scene centered around the “Warehouse” venue. They leveraged all three machines, spawning the funky Chicago House sounds of Frankie Knuckles and the stripped down, analog distortion-drenched acid of Larry Heard. Bellville High School teenagers Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May developed Detroit Techno based on 909 kicks, relentless 16th note hi hats and lush pads. And in New York, the 808 was the core of Hip Hop and electro, and a driving force in the breaker and graffiti subcultures birthed in the Bronx that took over the mid-Atlantic and the world. The 808 enabled the toasting and roasting scene to move beyond talking over B-sides and instrumentals, and towards original production. With hip hop, it led to an explosion of sound and technology, with the sound becoming more overproduced. With electro, it led to a remarkably versatile purism centered around 808 cowbells, lasers and loops like the legendary “Planet Rock”. Much contemporary electro maintains its early edgy feel.

Larry Heard produced the seminal acid house “Washing Machine” as Mr. Fingers.

The result of this technological, economic and cultural conflagration was fucking gritty, driving, fun music. People pushed the limits of those little boxes, hooking them up to distortion pedals, other guitar effects, and -most importantly- each other. Electro came almost solely from 808s, 303s and cheap synths. Acid techno emerged from New York and European producers layering several 303s, making leads, basslines and filigrees with the same tool. Each machine also reset to random patterns whenever turned on. Some of the biggest tracks of the 80s came out of many resets and tiny tweaks. The intersection between this randomness and the machines’ 16-beat structure are the heart of modern electronic music formulas. What resulted was a gorgeous, dissonant cacophony of lo-fi music recorded to cassettes and 8-tracks, and pressed to vinyl and sold like hotcakes if lucky. Capitalist record labels saw huge profit opportunities and quickly co-opted what they could. But the sounds, DIY nature and connection with Black and Queer culture meant there was only so far this could go. While hip hop grew massive, electro and acid in particular remained underground. This was even throughout later waves of rave music and “EDM” commodification.

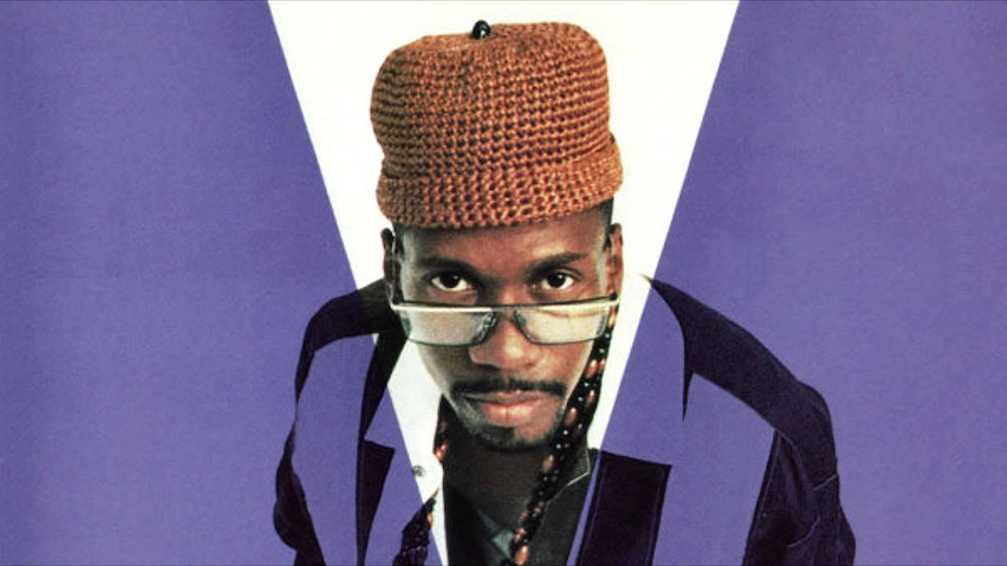

Above: Members of the Black-led Dodge Radical Union Movement (DRUM) on a picket line in 1968. Below: Afrika Bambaataa on the cover of the New York Times after the Bronx banned Zulu Nation. While there isn’t a direct lineage between these movements, both were responses to racialized deindustrialization. To learn more about DRUM, read “Detroit: I do Mind Dying”

These phenomena share many other roots. All came from working class, Black communities undergoing massive shifts. Much of this was due to transculturation, such as ongoing emigration from the Caribbean, or the maturing children of Southern Black families who came North during the second great migration. But they were also driven by ongoing de-industrialization, Capital flight and corporations abandoning cities as punishment for creating bloated “welfare states.” There’s an even deeper economic history, with roots in the first great migration, militant labor organizing in the 1930s and 40s, and the growing Black industrial middle class of the 50s-70s. Sometimes corporate abandonment and white flight was purely economic, but it frequently felt and ultimately was punitive. Regardless of intent, the impacts reinforced structural racism and stifled Black power. It’s strangely fitting that such musical movements emerged in these cities, in these contexts, as new forms of resistance and empowerment.

The motherfuckin’ saga continues

If both the economic conditions and music sound similar to right now, it’s because they are. While it feels both unique and terrifying in many ways, the current moment is much like that of the late 70s to mid 80s, and in some ways more like the early to late 1930s. The 30s featured powerful forces connected with the end of the depression, the peak of US labor militancy and the New Deal, but also rampant racism in housing and workplaces, the lead up to war, encroaching fascism, the first sights of deep oppression of the US left, and the beginning of modern military and police state. It was the birth of an era that not so ironically ended in the 1970s and 80s. And in that later transition, people were facing capital flight, union collapse, the oil crisis, “stagflation”, Reaganism, the drug war and the rapidly expanding police state. The difference between those two eras is that the early 80s were a fucking terrifying time for the left, the working class and more than anything for urban Black and Brown folks. It’s important to remember this history when considering our own moment.

In fact, the explosion of underground culture, art and music was one of the only good things to come out of the 1980s. Admittedly after forty years of Neoliberalism and the constant commodification of music and dissent, it may feel like even that expression is lost. I started working on this piece right before Russia invaded Ukraine, and I am only revisiting it months later, as people are genuinely afraid of nuclear war in Europe and beyond. Even I feel lowered hope at this very moment. But it’s unclear what the current transition will lead to economically, politically and musically. The recent return of Socialism as a palpable idea, particularly among young people, is very telling, as is this last year’s explosion of labor militancy and the global uprising for Black lives two years ago. And while we’re facing a protracted counter-insurgency causing some of that to already feel like ancient history, it ain’t! The tendrils of alternative understandings are firmly in the minds of many. As is the desire to organize, express solidarity, resist joyfully and get the fuck down to weird-ass music.

Top: Eliezer’s “Prime Minister,” which samples Margaret Thatcher. Middle: Art Was Art’s “Orwellian Nightmares.” Bottom: Anatolian Weapons “May That War be Cursed” multiple LP.

Buy “May that War Be Cursed” on Bandcamp. Proceeds support every day folks in Ukraine.

I’m obviously projecting my own views onto whole styles of music, with their own global and regional subcultures. Many folks enamored with acid and electro -including many DJs and producers- would think I’m full of shit, or that it’s just a fun way to party. But I’ve also observed the politicization of music over recent years. Much of the electro coming out right now uses dystopian samples on consumerism and has an 80s, “future-retro” kind of vibe. And several of my favorite acid disco producers (most notably Israelis like Eliezer and Red Axes) frequently include ironic or critical political samples in their music. Greek acid producer Anatolian Weapons created a whole album raising funds for working people in Ukraine while also taking explicitly anti-militarist stances (which is an important and nuanced distinction). I haven’t asked any of them, so I may be wrong, but the acid and electro revival is obviously global, driven not by constantly shifting Beatport genre names or algorithms, but by geography and joy.

There’s always room for a little theory

Responding to Marxism’s failure to explain how Capitalism saved Capitalism from itself, mid 20th Century theorist Karl Polanyi suggested social change resulted from great pendulum swings, rather than a series of teleological stages. Economic and political conditions accelerate in a specific direction until inherent contradictions breed inevitable, often sudden backlash. He saw the 1930s-50s development of European and US welfare states in this light, and likely would have seen Neoliberalism this way, too. While I don’t tend to hold grand theories of change (other than basic tenets of Marxism), I think we’re entering that kind of interregnum moment. The global pandemic, increased inequality, precarity alongside inflation, war in Europe, and the shifting of global power from the US and Europe to China and Latin America all indicate this. The moment is deeply anxious, but also angry, passionate and solidaristic. While it’s unclear if we’ll have a massive wave of organizing and a left upsurge, a rise in ecofascism, or a slow degradation of society, it’s almost certain that we’ll be churning out some radical art and culture, and hopefully fucking crazy awesome dance music all over the world.

That’s why I will always love acid and electro and why I chose the motto “33 revolutions on the turntable, one in the streets.” Thanks for reading, and support some of the classic or modern artists mentioned here if you can. See you on the dance floor and in the struggle.