Striketober, Halyna Hutchins, and the Folks that Brought Hollywood the Weekend

Remembering Victories and Losses

I worked on this piece over the days between the IATSE strike vote and the tragic death of Cinematographer and IATSE member Halyna Hutchins. It’s bitterly ironic that she died after supporting the IATSE strike vote and her fellow crew members walking off set from the film “Rust” to protest dangerous working conditions. And it’s telling that what killed her was a prop gun that had already misfired, yet that the non-union Assistant Director, the film’s Director and Actor/Producer Alec Baldwin all decided was safe. Deplorable conditions and prioritizing profit and hierarchy over worker well being were precisely why IATSE members were ready to strike last week.

Halyna Hutchins image shared by IATSE

Tens of thousands of US workers and countless more internationally are engaging in militant job actions this month. It’s a potentially pivotal moment for the labor movement, and so hard to ignore that even parts of the mainstream press are embracing the term “Striketober.” Local actions, coordinated strikes and even simple strike threats are reverberating within and across industries, winning major gains for workers. This is the case for the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), who finally won Hollywood workers the weekend, hours before a strike that would have hobbled an entertainment industry dominated by tech companies and streaming providers. The IATSE threat also drastically elevated press coverage of the many recent successful or ongoing strikes, and will hopefully embolden more.

Strike action has already been mounting for months. Over 600 workers at a Kansas City Frito’s plant walked out after negotiations failed in August, protesting 12-hour days and 7-day workweeks. They settled after two weeks, getting at least one guaranteed day off. A month later, 200 Portland workers in a Nabisco bakery walked off over similar conditions. This spread to plants in five cities and a distribution center in Atlanta. Well over 1,000 Nabisco workers struck, some for over a month. They were followed by 1,400 Kellogg’s workers, who are still on strike as I write this. All of these workers are with the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers’ International Union (BCTGM – a mouthful, I know). This was the first time the Kansas City local has struck since 1973, the union’s first strike against Nabisco since 1969 and Kellog’s since 1985.

Then came October, which has already brought the 60,000 member IATSE strike vote and an active United Auto Workers (UAW) strike by over 10,000 members at John Deere. On October 11th, 24,000 Kaiser Permanente hospital staff granted strike approval in California and Oregon. 3,000 in Hawaii joined them this week. I’m sure I’m missing other actions, too. Then there’s the rolling strike of hundreds of thousands of workers across industries in Korea, which culminated in a half million people one-day general strike. They are demanding radical changes in the economy, including expanding healthcare, nationalizing certain industries, and a just transition. They’re planning mass actions for the next two months, leading to a nationwide disruption in January 2022. This, too, is ironic, as the recently launched Squid Game -“the biggest Netflix show ever” – was inspired by Korean mass strikes of the 1980s, and current strikers are using Squid Game imagery. Life imitates art imitates life.

It might be preemptive to say that this will turn into a sustained period of militancy. And it’s tempting to dismiss, as there have been similar moments in recent years, both inside and outside the labor movement. As I’ve highlighted before, the 2008 financial collapse, 2011’s Occupy Wall Street, 2012’s Chicago teacher strike and the first wave of Black Lives Matter protests felt similar. But while they radicalized a whole generation of young people and created massive events, they didn’t transform into sustained action. Ultimately, I think they were as much premonitions as they were movements. They set the stage for 2018 teacher strikes and last year’s global uprising for Black liberation, both of which were more sustained and became the largest and most geographically movements of their kind in… forever? But even these aren’t the same as right now, which is centered on economic action in the private sector.

Economic action has always been the main locus of power for working class people, and strikes the most effective for getting economic and social goods, particularly when they create “strike waves” spreading across industries or lead to general strikes. There is a treasure trove of US and international labor history showing this is to be true, whether via the eight hour day strikes in the late 19th Century (such as the Haymarket riot), the 1933-34 general strike wave in San Francisco, Flint, Toledo and Minneapolis helping bring union protections and New Deal programs, or the 2018 “Red State Revolt” of teacher strikes in West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arizona and other states winning victories for teachers and students. There’s even a growing body of compelling work suggesting industrial unions and working class political parties were the primary vessels for bringing Democracy to the world over the 20th Century.

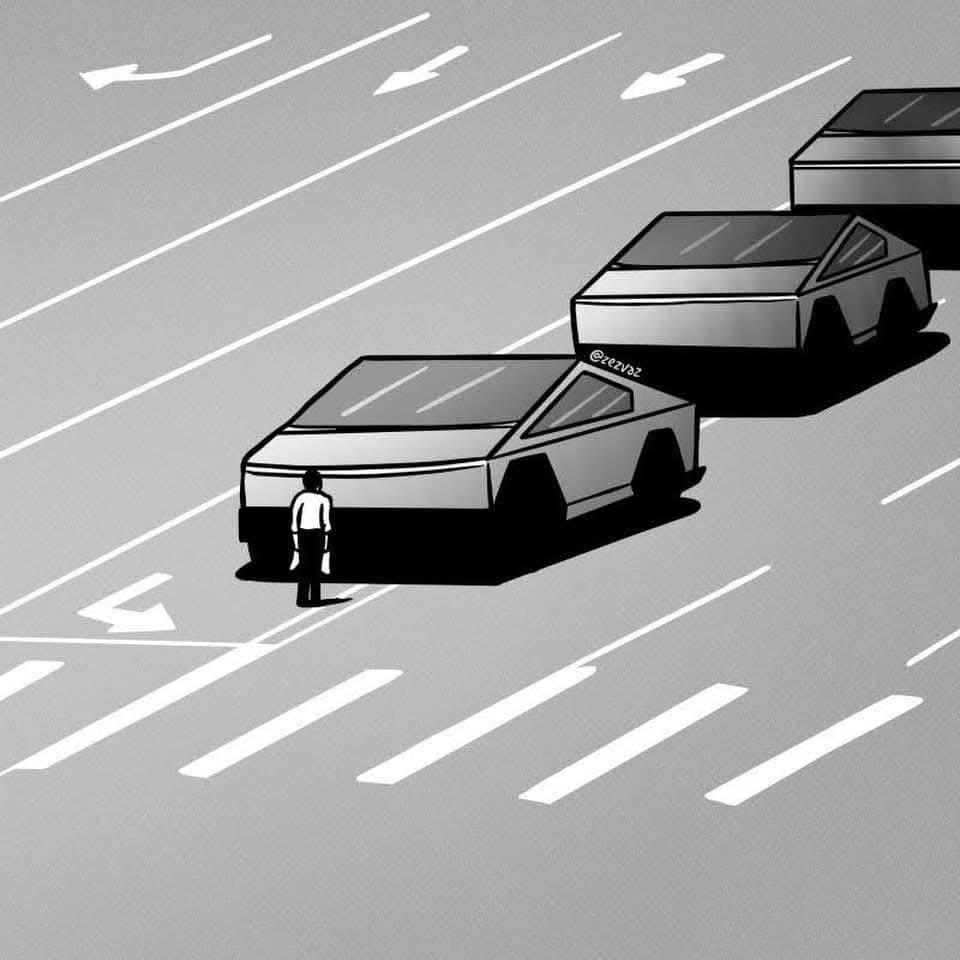

Strikes and union power

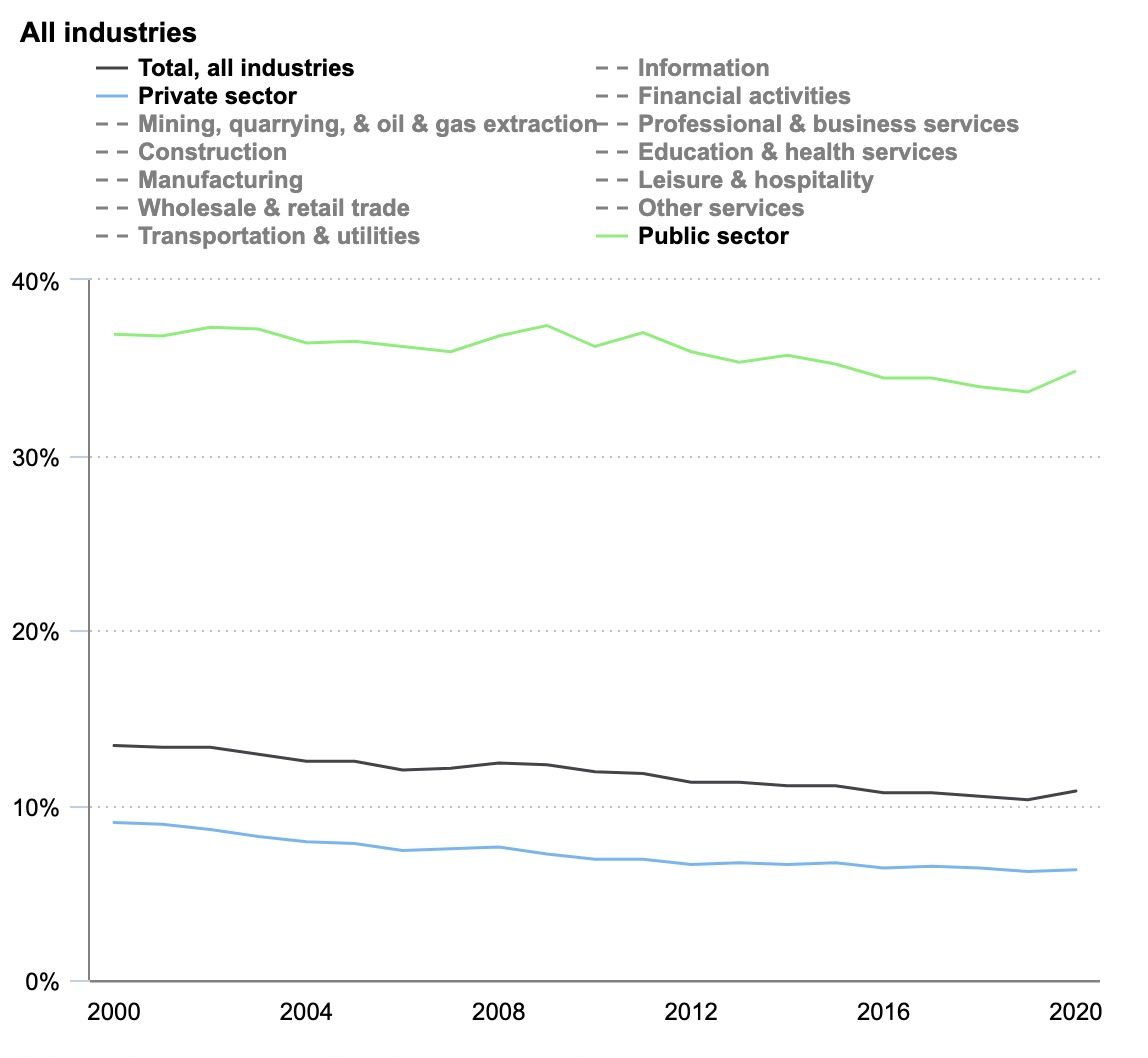

Labor Union Membership in the United States, Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Wikipedia

There’s a well-known correlation between the decline in US union power in the 1960s-70s, the decoupling of wages and productivity, and the collapse of the “Welfare State.” We went from 33 percent unionization in the mid 1950s to 11 percent today (35 percent of the public sector, but only six percent of the private sector). There was also a decoupling of protest and economic action. While both decreased in the 1970s and 80s, by the late 90s US protests against neoliberal globalization were exploding. But they were rarely linked to strikes or the broader labor movement. Since then we’ve seen frequent mass protests, such as with the Iraq War in 2003, Occupy, or marches against Trump and for women’s rights, science and more. All were numerically huge but generally weak.

The one exception to this is the inspiring wave of Black liberation protests in the wake of police state murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Manuel “Manny” Ellis, among countless others. But the victories achieved there are partially due to the real or perceived threat of riots, which are a form of economic action. These wins are also easier to roll back after a movement dies down, and calls to “defund the police” are already waning. But crucially -as with the airport occupations killing Trump’s attempted immigration ban- they demonstrated that threatening the bottom line is one of the only ways to counter the ruling class.

What’s unique about this moment is that the majority of active and pending strikes are in the private sector. These were common in the post-depression era (and in the economic recoveries after earlier depressions, panics and other funny named crises). But they’ve declined precipitously for decades. The only places where they are still relatively common is in healthcare and service industries, but even those are mulower than their heydays. That’s why private sector action is crucial. It’s also clear that the biggest strikes, threats and new organizing drives are in the industries reaping the greatest profits throughout the pandemic by exposing their workers to the greatest risk. We are finally seeing real movement at places like Starbucks and Amazon, previously considered unorganizable. The global media are paying attention, with extensive coverage of outlandish corporate profits for Amazon and grocery stores, billionaire of the week in space, and yawning inequality. Maybe this is why Socialism is more popular than ever in the US and the UK?

One particularly important thing about IATSE is its proximity to the media. Hollywood loves talking about Hollywood, as exemplified by the massive amount of coverage of the leadup to the strike in basically every industry outlet imaginable. Sure, this is because Hollywood is ridiculously self-referential, but it’s also because much of the news these days -especially in entertainment- is subcontracted, piece rate, or by people with other entertainment careers moonlighting in some way. There are as many self employed or contract journalists in LA as there are budding screenwriters, IATSE members and waiters. There’s also the novelty of a union that hasn’t ever gone on strike doing so in the middle of a pandemic, and against companies like Amazon and Netflix, both known disruptors and despised to varying degrees by union members and studios alike. The conditions and escalating actions were such a social media and IRL powder keg that -while many members justifiably think it didn’t go nearly far enough- the contract won things they had wanted forever.

Before discussing the lead-up to the IATSE vote, it’s important to clarify that conditions are likely as bad -or worse- for all of the other workers mentioned above. The majority of IATSE members likely receive better pay than most, they originate out of craft unionism and tend to be more specialized, and many members likely have social capital based on their industry. But none of this (or conditions for teachers, doctors, nurses or other “professionals”) should matter in the face of working class solidarity confronting oppressive workplaces or bosses. I firmly believe a worker is a worker and a Capitalist a Capitalist, and my favorite pithy labor quote -which comes from the very well-paid International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU)- is “an injury to one is an injury to all.” That said, the prominence and media hype around the IATSE vote and the death of Halyna Hutchins make this a perfect example of why we need a militant labor movement.

How IATSE got here

Conditions in Hollywood have always been terrible for basically anyone other than executives, A or B-list actors and Directors, and a few folks who get lucky stringing things together. It’s common knowledge, and I’ve had family members and friends (some in those lists, many not, several in IATSE or the Screen Actors Guild) share this with me over the years. This is significantly worse for “below the line” staff (basically everyone who isn’t a producer, director, actor, or writer- so on the fucking poster). These are the people who get squeezed over variable labor costs, through lengthening shooting days, cutting costs, removing meals or just gutting scenes from a script while already on set. It doesn’t help that IATSE was originally a mob-controlled union with weak bargaining power, or that the Hollywood studios have gone through decades of cutthroat competition and consolidation. And all this was before the Amazonization of Hollywood.

This all deteriorated further with the launch of streaming services in the mid 2000s. Driven by Netflix, the new providers negotiated separate, lower pay and benefit rates when they were just baby “startups” (isn’t that cute). Apparently the rationale was that they had a tiny market share, would provide very few jobs, and were taking losses. While I don’t really want to fault the union here, I also find it mind boggling that they (and traditional studios) didn’t see the freight train of streaming content wars coming. But hindsight is 20/20 and this is how it played out. Competition skyrocketed when Amazon entered the scene. By last year, there were over a billion global streaming service subscribers, and streaming accounted for about 80% of the $32 billion US market, up from 37% of $30 billion in 2016. They are a behemoth that simultaneously drives up spending for A-List actors and directors while driving down wages for everyone else.

Conditions went from bad to worse under COVID, where studios initially shut down or drastically reduced operations, then pushed workers harder than ever to play catch up. The horrific content war norm grew exponentially worse for workers below the line. Already excruciating long days were extending out to 16, 18, 20 hours, with often very little time between shifts and no guaranteed weekends (even though actors are guaranteed weekends). Studios were ignoring the majority of meal breaks and instead opting to pay a scaled “meal penalty” per half hour they didn’t give off. The problem with this is that the low starting rate of $7.50 for the 30 minutes hadn’t been renegotiated in years (again, at least in part on the union). So not only were the studios always incentivized to drive workers harder, but the penalty was tiny. This great video explains all of this and more.

In this year’s bargaining, the union was asking for at least 54 hours off for weekends and 10 hours between shifts, along with increases in base rates, alignment between streaming studio wages and others, not absorbing healthcare costs, and helping fix issues with their pension. The studios, represented by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), were basically trying to squeeze blood out of a turnip, proposing wage cuts, a dual healthcare system (where newer workers pay more), and other take-aways. The union bargaining team and members weren’t having it.

As is often the case, the movement towards the strike vote was really driven by rank-and-file members, here via viral videos and other social media. It helps when you have a bunch of creative types in a union local. IATSE members took a strike vote the weekend leading up to October 4th. Over the course of three days, 90% of the over 60,000 members voted, with a whopping 98.6% voting to strike. This would have been one of the biggest private sector strikes in the United States in decades.

My mediocre attempt at a movie poster celebrating Hollywood weekends

They set a strike launch for midnight on Monday, 10/18. Employers conceded on the most important demands on Saturday. The Tentative Agreement included won 10-hour turn times and 54-hour weekends, increases in base pay, meal penalties and streaming pay rates, Martin Luther King, Jr. Day off, and a three percent retroactive Cost of Living Adjustment for the year. Many IATSE members justifiably don’t think it’s enough, but it seemed for several days that they would vote up the contract. That was, of course, all before the death of Halyna Hutchins. Who knows what might come of things now? But it’s a profound understatement to say conditions are still explosive.

The events surrounding Hutchins’s death are awful. “Rust” is a low budget film starring and produced by Alec Baldwin. This means Baldwin is partially responsible for the film’s budget, something neglected in most press. The film’s Assistant Director has a history of cutting corners and creating unsafe working conditions. Things were already so bad on set that the entire camera crew had walked off in protest the day before. When they came back at 6:30am the day Hutchins was killed, the production had brought in non-union replacement workers -Scabs- willing to do worse for less. They threatened to call the cops on the union crew. The press details are murky on what happened, but Hutchins was a union member who seems to have been openly supportive of the strike and advocated for her crew’s safety before being killed. The Assistant Director handed Baldwin a gun that had already misfired and yelled “Cold” (implying no live rounds). Baldwin pulled the trigger, killing Hutchins and injuring Director Joel Souza.

This is basically how it is everywhere. Film studios, owners, the ruling class… they’re all driven by a system that demands relentless cost cutting in order to maximize profit. Alec Baldwin is literally the most satirized example of a well-meaning Hollywood liberal. He probably feels terrible about what happened and wishes he hadn’t pulled that trigger. But it was ultimately his need to keep costs down that killed Hutchins, which is more willfully negligent than an honest mistake. This is why IATSE voted to strike. This is why Amazon and Starbucks workers are organizing. This is why there is about to be a huge wave of healthcare strikes, even as tons of nurses and other staff are walking off jobs. And all of this is on top of the “Great Resignation” happening throughout much of the US economy, where working folks are using weapons of the weak because they either don’t have the information to organize or just hate their shitty jobs.

The last few weeks of IATSE tension and the massive press it’s gotten (and, sure, why not, Squid Game) are giving working class folks a glimpse into each other’s lives, and the growing notion that the oppression they face is similar. Even if unionized IATSE and John Deere UAW members make much more than unorganized Amazon or Wal-Mart workers. Even if most nurses have degrees that many folks will never get. Even if Korean strikers speak a different language under different cultural conditions. This is a moment for class consciousness and potential action, and can drive many, many people to the sense that organizing and economic action gets the goods. Even if this precise strike wave doesn’t sustain, it is fundamentally shifting the narrative on what it means to be part of the US working class and creating the space for a more internationalist class consciousness. And while these are ultimately insufficient conditions for a transformed labor movement, they are absolutely necessary.

One final and important thought. There are countless ancillary benefits to all this, largely around how workers conceive of themselves as a class, and around dignity. One is the growing realization that industrial and craft union work is skilled labor. Comedic examples of this abound in the UAW strike, where one scabbing manager severely injured himself on the first day of the strike and another crashed a tractor into an expensive piece of machinery. Another is that union workers and their actions are being humanized. Images of workers in several of the strikes have gone viral, including one of a Kellogs striker in pouring rain that was shared by Newsweek and other major news outlets. These are places that rarely ever cover strikes with any consistency. The profoundly tragic death -the martyring- of Halyna Hutchins will likely keep these flames flowing through popular consciousness for at least a bit. It’s up to all of us to remember her, the countless other forgotten workers, and the movement we all must co-create together to transform society.

To learn more about Halyna Hutchins and her short but impressive union career, please see her website at http://www.halynahutchinsdp.com/bio

Rest in Power, Halyna.

An injury to one is an injury to all.

Solidarity forever.