Part 1: The What Behind the Woo

This site isn’t just a hotbed of highfalutin left wing propaganda. It’s also a celebration of the irreverent, self indulgent, adorable and abhorrent world of festivals and raves. And sometimes it’s both… as I’ve been known to ruin dance floors with a well-timed “I blame Capitalism” blurt, or derail serious meetings with jokes only someone who’s really gone there understands. Figured I might as well ruin my nascent blog by getting all Marxist on the woo-woo, or at least offering some thoughts on the who -and what- behind the woo. So here’s a two-parter about what’s really so transformational about festivals and why there are suddenly so many Conspiritualists, narcissists, and paranoid anti-vaccers in the scene.

TLDR: It all comes down to alienation and analysis.

Like many subcultures the world over, the rave and festival scenes are filled with outsiders finding common ground around their quirks. Parties are often profound and beautiful spaces for connection (yes, even sober), and for many people, the first place they’ve felt fully accepted. It was certainly the case for young 17-year old me, when I traveled six hours to Salt Lake City, put hair color in my shitty white boy dreads, ate the “candy” off my sweaty neck, and giddily stared into a filthy bathroom mirror at the hideous rainbow explosion I’d become. I’ve heard many similar stories, all transformative in a way that’s hard to explain to the uninitiated. I’ve never been religious but my partner was for a time. She says the feelings are equivalent.

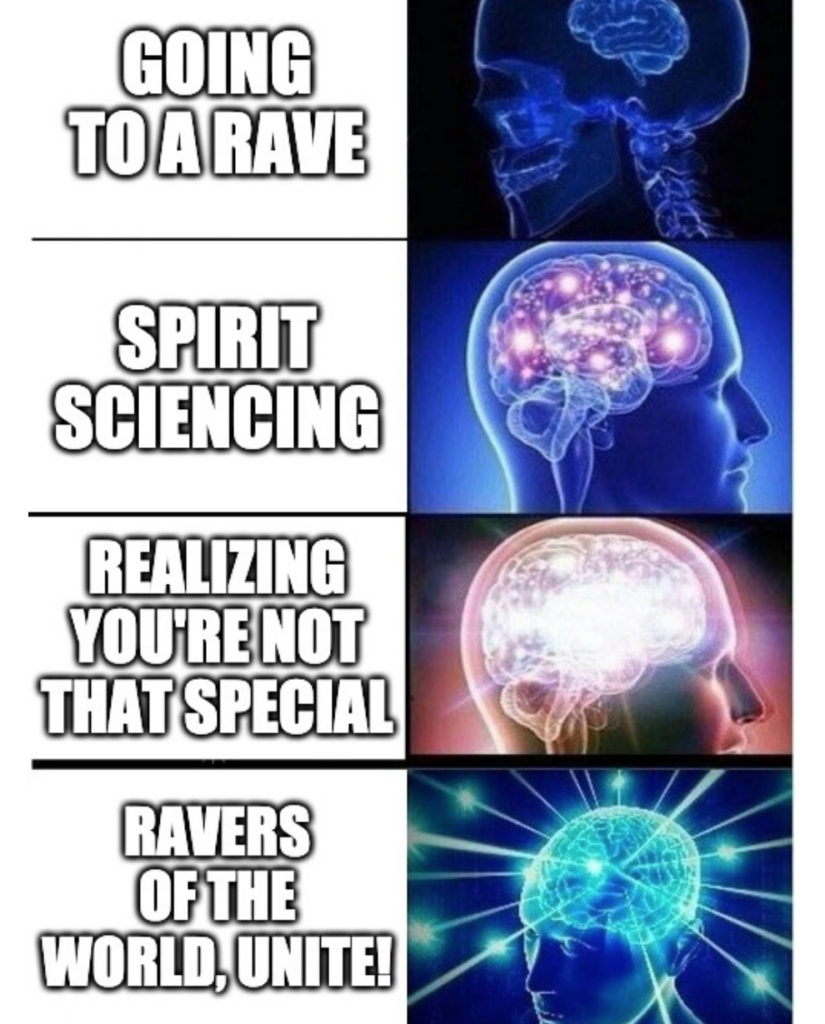

Similarly, there’s a sense of uniqueness in subcultures originating on the margins. In party scenes, it’s often associated with the “transformational” nature of the experience. The newness is profound enough on its own, and doubly so when connected to Ideas on music, art, liberation, and all manner of spiritual experiences (and, of course, enhancements). I’m not opposed to any of this and find it cathartic. In many ways, it has sustained me for going on 25 years. Although I prefer knowing there are tons of folks out there doing the same shit I am on a Saturday, rather than thinking my small but dispersed pocket of weirdo friends is different. But I digress.

There was a palpable sense of “transformation” in the festival world of the mid-late 2000s, before it was officially big business. The scene was exploding but accessible, and changing many lives for the better. Feather leathers and hipster headdresses weren’t yet all the problematic rage. It was another wave of idealistic young people imagining a flattening of social hierarchies and a potentially better future, just like the hippies, punks, B-Boys and ravers. Many people tried to explain it in spiritual terms, and some launched careers out of it. There was even a low rent TED Talk about how festivals brought collective consciousness. It included the intimate festival I promoted for a decade on a big “Transformation Map”. That felt pretty good.

That world -that aesthetic- was of course already deeply commodified, as all subcultures are much quicker than anyone wants to admit. But there was still an authentic innocence, before a decade of shark jumping, mega corporations gobbling up the commercial parties, and things like “transformational” festival promoters across the world banding into the 2017 “Global Eclipse Gathering” (or as my circle calls it, the “Solar Shitstorm”) and its money-grubbing Patagoa Pandemic follow-up. At some point, even the self referentially ironic parts of the community get sucked in, such as the “satirical” conspiritualist jackasss JP Sears going full fashy and monetizing his own child. Life mimics art, or maybe art memes life.

I don’t want to belittle anyone’s very real experiences. I just want to reframe them. I still love parties and plan on attending and promoting them when they are safe. The collective effervescence is real and travels through everyone when the vibe is right. Music and substances have intense impacts on individuals and groups, generally for the better. And, although I personally identify as an Atheist, I think even the spiritual components are powerful and potentially positive for many. One of my own central tenets is that human beings have a desire to believe in something. The problem is that they conflate the act of belief with what they believe in.

But there’s much more happening on relational and material levels. For a moment, a day or a week (say, at Burning Man), people are co-creating their experiences in ways that they don’t get to at work, in day to day life, or in most consumer entertainment settings. This is true even though they’re still engaging in a transaction. And, while we may not notice, the co-creation goes beyond the “vibe” or the “set and setting” or the “temporary autonomous zone”explanations born of spiritual or person-centered explanations. There is a fundamentally relational experience of being in community, and a material one of doing work that directly benefits you and those around you.

It’s about people people feeling less alienated from each other, their own labor, and even the planet. It is about the work we put into our costumes, camps, DJ sets, or (often exploitatively long) volunteer shifts. Moreover, it is about being in a space of work with others and directly participating in and benefiting from your work. It’s the closest experience to real solidarity that many folks get in modern consumer culture. It’s as much like attending a protest or organizing a unionized workplace as it is about being in a spiritual center or church. And while these are psychologically similar types of experiences, the material, relational sides are tragically ignored.

Alienation is a fundamental feature of modern life under Capitalism. Most of us spend close to half of our time producing, serving, or selling products created with our labor for someone else’s profit. We frequently have no direct relation with the people profiting off of our labor. We create things that are not for us, in volumes that aren’t useful for anyone. At some point, the return for daily work becomes greater for the person profiting than it does for us. This is what Socialists mean when they say all profit is surplus labor. Someone else makes money off you, has all the power over you, and you have to sell yourself to them to survive.

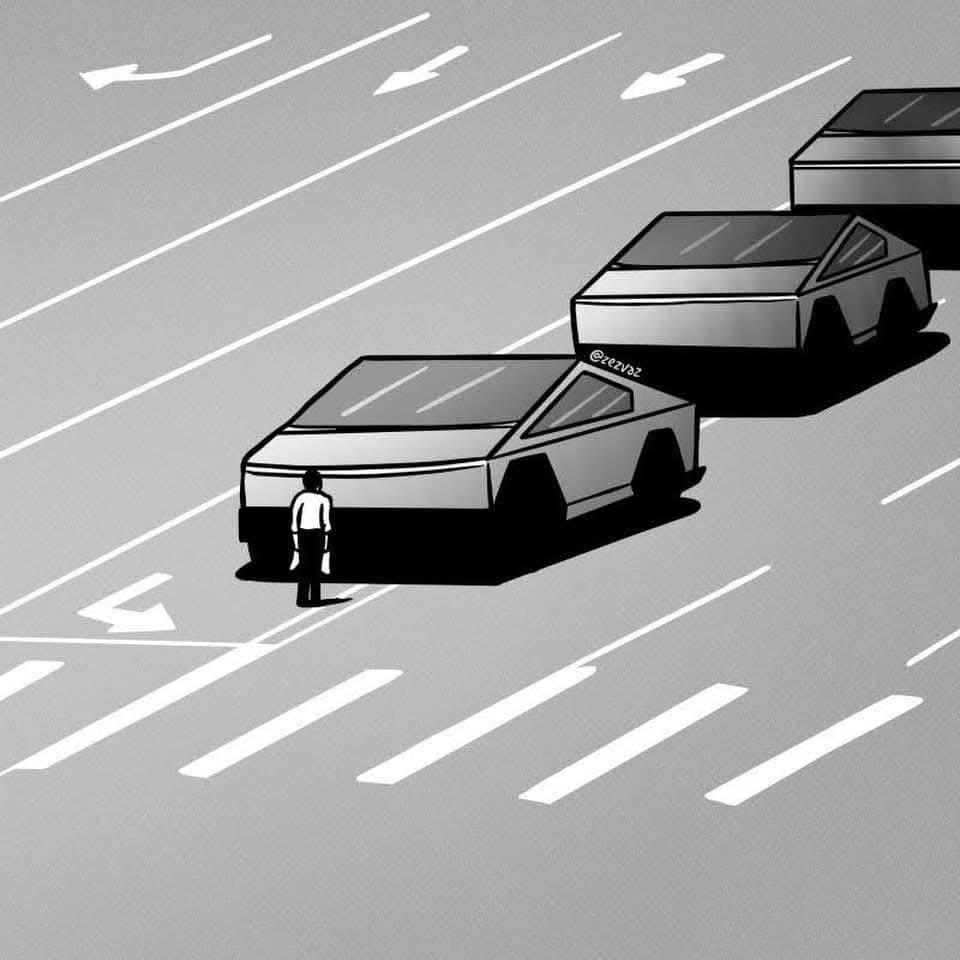

Alienation causes disconnection from other people and the planet. Capitalism forces us to commodify ourselves every time we look for work (competing with others on the market), every time we go to work (worried about who is out-performing us), and every time we doom scroll social media in an effort to escape the inanity. It destroys the planet and reduces life to commodities. It treats our experience of nature as a product while simultaneously avoiding any responsibility for its destruction and -worse- trying to convince workers that somehow we’re the problem and flushing our toilet less or buying an electric car is the solution.

There are many ways in which people try to get around this. Sleep, religion, sex, drugs and rock-and-roll have always been ways for working people to try to overcome alienation and many other social and emotional traumas. In some cases, these ubiquitous coping mechanisms are accompanied by more complex ones centered around solidarity in work or community. Humans have always used groups to connect, cope and organize, whether through churches, unions, social clubs, chat rooms, brand identity or whatever. Frequently, these take shape as resistance or empowerment, and sometimes it all coalesces into spaces of combined, active work towards celebration and resistance.

For me, and I think for many, the rave and festival community is at its best a temporary resistance to this culture of market domination. The early rave scene, particularly in the UK in the late 1980s, was a highly radicalized, youth-driven, left wing celebration of resistance to domination under Capitalism. It was literally ran by roving bands of squatting British youth occupying spaces, refusing to pay rent, fighting police and partying their faces off to music created by gay Black men in Detroit and Chicago. They didn’t like Margaret Thatcher. They didn’t like Ronald Reagan. Many of them didn’t like Capitalism. But they sure liked to party. And that’s ironically the rub, as I’ll explore in part two.

Some of you are likely thinking “Yeah, OK. So raves are like churches and unions. We already knew that.” I’m not saying anything particularly new, and some of this is even referenced in places like the 10 core principals of Burning Man (although I think they’re problematic) or Hakim Bey’s concept of Temporay Autonomous Zones. But most reflections on these communities focus on the individual as the locus of action, and often the “spiritual” as the act of transformation. This lessens the importance of collective action and -ironically- masks core contradictions within transactional and often exploitative or culty relationships that emerge from commodified woo-woo spirituality.

In short, if we were to emphasize solidarity over woo-woo spirituality and pseudo-sceince, we’d likely forge deeper bonds and feel less alienated in our day-to-day lives. We’d certainly be more likely to turn to things like workplace and community organizing, or at least volunteering and political engagement, instead of chasing the next party or fix (not that I don’t like a good party). Crucially, a relational, struggle or solidarity-based approach to these communities also helps avoid some of the weird traps that transform hippies into right wingers, seemingly overnight. For when we’re in actual community, we form not only identities, but also the potential for analysis. But you’ll have to read part two for that.