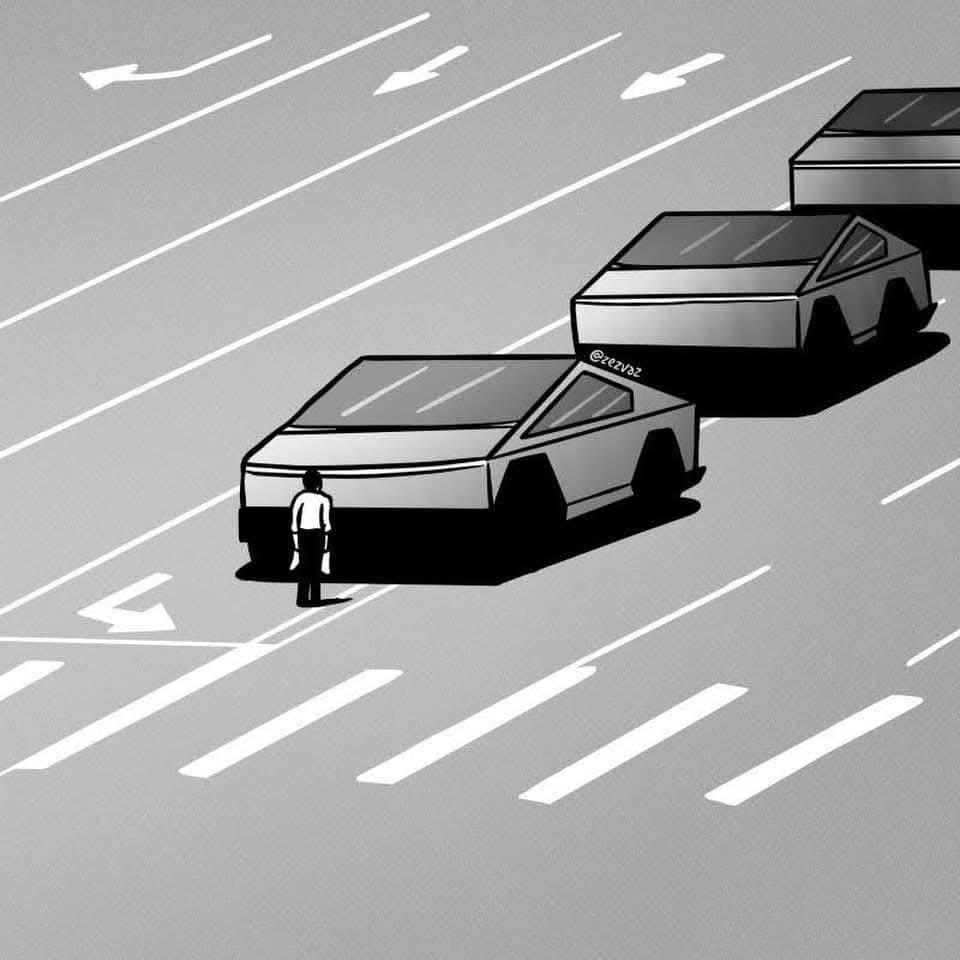

Artificial Art, Creative Crisis, and the Contradictions of Capitalism

Two versions of MidJourney prompt: “Dialectical Materialism Class Consciousness Artificial Intelligence Soviet Kitsch”

The explosion of cheap and uncannily realistic Artificial Intelligence-spawned art has caused equally prolific emotional responses across the social media universe. Countless Lensa users and self described MidJourney artists are intoxicated by the ease with which AI channels their self portrait or movie mashup aspirations. Some of my more optimistic design friends are creating gorgeous mixed pieces inspired by or using AI. Others are justifiably upset about what a flooded AI art market means for their already low chances of payment for their labor, honor for their ingenuity, or recognition for their intellectual property. There’s rampant recrimination and accusation of selling out or luddism, all amidst an inundation of cute but generally trivial content. The fact that all sides have valid arguments only amplifies the intensity of emotions and critiques, both practical and philosophical. This is often the case during major technological disruptions.

But many boosters seem to overestimate opportunities while many skeptics miss key problems. AI art can be empowering, but only under transformed economic conditions and greater social trust. And the risks are both more banal and more insidious than most realize. Yes, AI will diminish demand for original digital art, further alienate artists from their work, and replace some lower level design and content writing positions. But the core material problems will be via exponential exploitation of worker productivity, Capitalist gridlock in Copyright, and the final nail in the coffin for the era of artist wealth creation through physical mass media. Exploitation will be terrible and widely felt. Copyright confusion will be intense, but limited to firms and investment markets. The final nail will be barely noticeable for most artists, other than as a forsaken future for the few still believing the hype machines. I explore all three outcomes below, weaving the technological, economic, ideological and emotional factors unfolding, and ending with a vision of actual AI arts empowerment.

In the long run, I’m an optimist who believes technology’s potential to liberate working artists and decommodify human expression. As with many prior advances, creative AI could and should make life better for all. It joins recent breakthroughs in areas as diverse as cold fusion, carbon capture and quantum computing to remind us that better futures are within our grasp, although the horizon is blurry. But I’m convinced that while these technologies are likely necessary for our social survival, our economic system renders them insufficient. The only path to leveraging them for liberation is in a post-Capitalist society. Realizing this begins with and requires moving from a technological to an economic understanding of social change, and towards building collective solidarity and trust. Absent this, AI and other technologies at best hasten the economic crises that precipitate revolutionary change. At worst, they fit snugly into Capitalism’s voracious exploitation of resources and time, reinforcing contradictions without transformation. Those painfully predictable paths make me a short-run skeptic.

The most immediate, painful disruption from AI will manifest via dramatically increased productivity expectations (rather than job loss) for contractors and firm-based, wage earning creators (rather than working artists). The competition will not be with AI itself, but with one’s own and others’ abilities to push hourly and creative limits to satisfy demand for constant, near instantaneous proofs of concept and first drafts. Productivity expectations will skyrocket while wages stagnate. The pool of potential human competition will swell to whatever the databases enable. Creative workers will be incentivized to adapt to all new AI tools, to withhold information and tricks from each other, and to respond to requests whenever asked. Full AI automation will remain a threat to bludgeon the workforce and squeeze more hours, but implementation will not be as widespread as predicted.

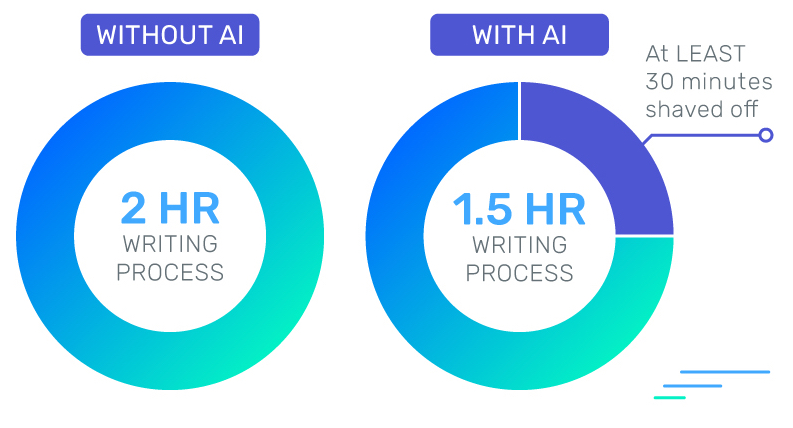

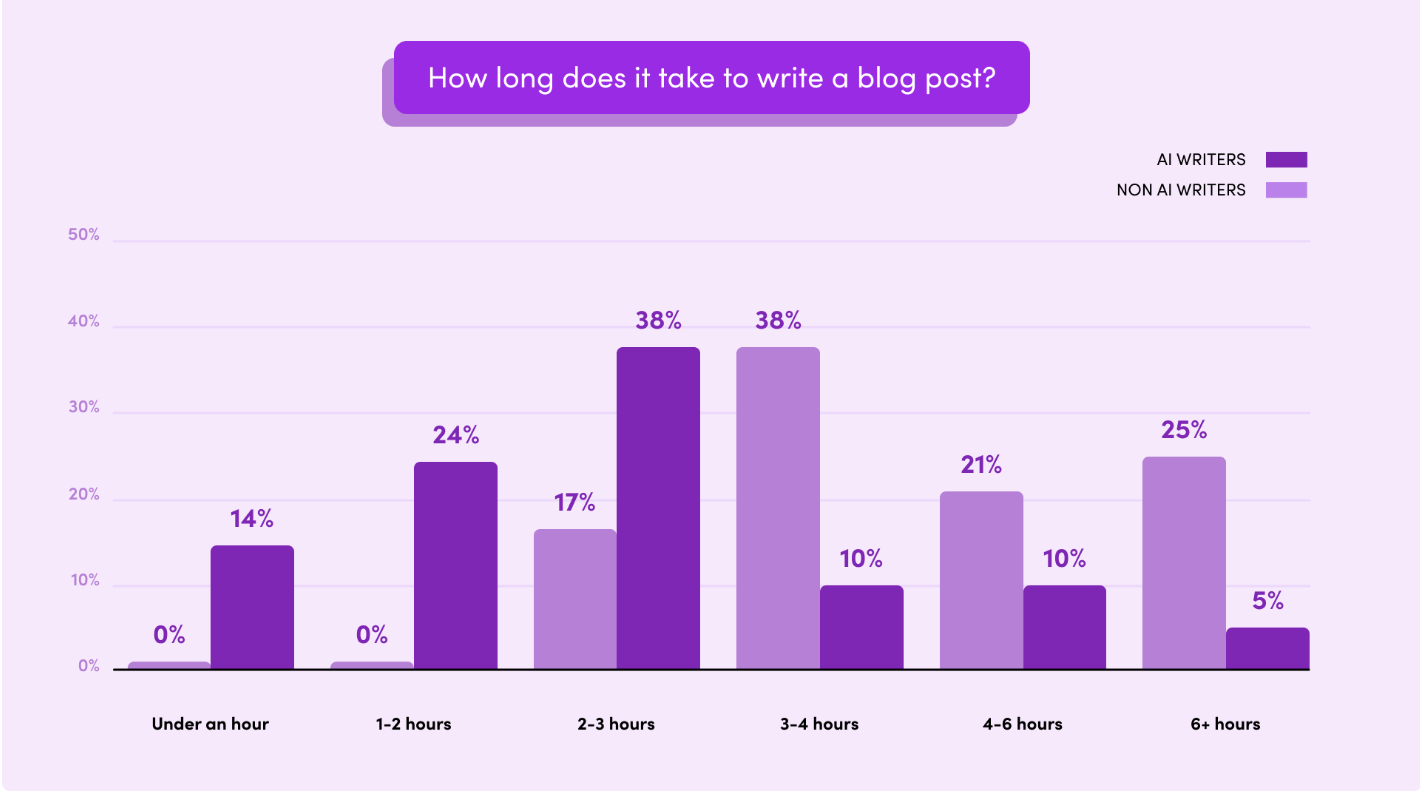

Some random AI writing ad I downloaded. There are countless others.

Some random AI blog time analysis I downloaded. The emphasis on time saving is misleading, in my opinion.

My reasons for emphasizing exploitation over job loss are many and varied, and I’m not going to expound on theories here. But I will say that -at a fundamental level- Capitalism needs working people spending money to survive. AI’s potential economic impacts are so extensive and interwoven that mass reductions in force would reveal foundational economic contradictions. Whether consciously recognizing it or not, Capitalists are disincentivized to automate beyond a certain point. This has always been the case. Moreover, firms have deeply embedded practices, systems and cultures that take generations to change, just as they have with every other major shift. But they are good at quickly adapting for productivity gains, particularly when they can make it look like these gains benefit workers. The AI workplace transition will be towards similar numbers of people churning out much greater content, rather than many less doing equivalent amounts. I’m already seeing Facebook and Google ads heralding creative AI as liberating work, when it’s just the same old exploitation, repackaged.

A quick sample of historical “time saving” technology reveals why exploitation should be the greatest concern. Tools ultimately intended to serve profit are always framed as liberating, and creative AI companies are adopting language that dates back to at least the mid 20th Century, when American manufacturers anxious to maintain World War II-level productivity pivoted new industrial technologies and propaganda tools towards home appliances and workplaces. Their in-home washing machine, dryers and dishwashers were advertised as freeing housewives to pursue leisure activities and personal growth. But mounds of evidence suggest the opposite happened. Women in the home took on even greater workloads, and the patriarchal social reproduction of labor under Capitalism ensured even those entering the workforce were still expected to cook and clean. The same was true for a wide range of products, down to the smallest gadgets. Most led to more exploitation in the home, not less.

A 1940 washing machine ad centering time saving

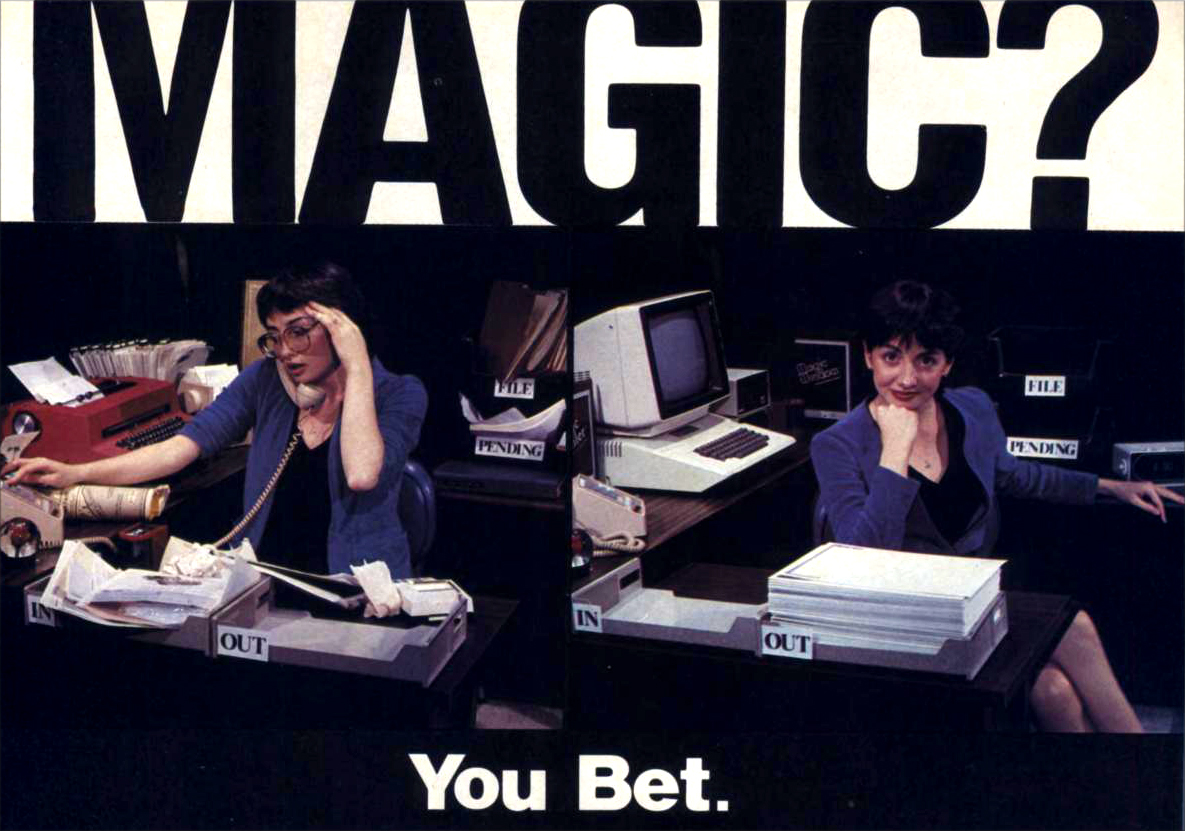

A 1980s computing ad… apparently centering decluttering your desk

In the workplace, time-saving as liberation rhetoric is exemplified by “blue collar” industry innovations such as the Universal Product Code (UPC), just-in-time delivery or automated scheduling, and “white collar” industry innovations such as word processing, computers in general, and email. All were heralded as time-savers for workers, and could very well have empowered generations, just as the ads say AI design and writing could do now. But the truth is that they de-skilled work and extended hours, particularly for what little white collar women’s work was available in the 1960s-1980s. The only workers they emboldened were in new mid-level management and bullshit “assessment” jobs. All of this is inherent to innovation under Capitalism, which is fundamentally about profit, not quality of life or experience. Yes, much innovation is legitimately beneficial, and it’s impossible for me to imagine doing my own job without these tools and many more. But it could be different and so much better for all of us.

AI stacks on the crushing effects that innovations such as gig work and pandemic-driven adoption of online meetings have had for creatives and white collar workers. We all forgo walks down the hallway or commutes to a client’s office and instead meet back-to-back. We meet at all hours in all places, yet we’re perennially late to our own lives. Now the creatives among us can add in cycling through infinite design proofs, first drafts of marketing emails, and… basically whatever. Some will justifiably claim churning out content makes their jobs easier. But it’s difficult for me to imagine this leading to generally easier work, rather than massive productivity growth, and I guarantee exploitation will be greatest for historically oppressed folks. Of course, most people are too busy trying to figure out their daily routines to fret about what AI means for their schedules. But -regardless of our awareness- if the majority of “time saving” technology leads to more work, then there is something else behind the problem. It’s just Capitalism.

But what about the philosophical, ethical and practical concerns for working artists and writers? The folks taking memorable photographs, creating gorgeous murals, or penning original poems, however sublime or cheesy it may all be? They act within market Capitalism, but their creative processes are more artisanal than industrial, and the markets for their goods are historically more akin to precious commodities than mass consumer goods. Do they face the same concerns facing wage earning creatives? Will lower income art consumers who want to adorn their walls still be willing to pay a couple hundred bucks for something wholly original when they can easily enter some terms into a generator, see their own ideas manifested, and pay a small fee and purchase a print? How will working artists reconcile their frustration with consumers for doing this when they, too, have a longing to bridge the gap between what they imagine and what they produce? If there’s no human creative process, then is AI art even art?

Most commentary is about how AI means working artists won’t be able to make a living selling their original art, which will be inherently devalued by ease of access. There are tons of memes and pithy comments comparing artists to musicians, basically amounting to a “welcome to the club.” This makes sense, as AI and algorithm-based streaming services destroyed what little royalties most musicians received years ago, and they’ve long faced media empires under the likes of Spotify CEO Daniel Ek, who recently proclaimed “it’s not enough for artists to release albums every three or four years to stay viable.” But while the bitterness is understandable, this framing makes it look like artists and writers have had it good up to now, which couldn’t be further from the truth for most. But it does get close to an important phenomenon I think doesn’t receive enough attention. The very ideas of profitable art, writing and music via mass consumption were uniquely 20th Century phenomena.

Prior to mass media, the majority of “successful” writers and artists made livings through wealthy patrons. Musicians and actors were similar, although they also performed live to everyday people. In reality, most modern working artists haven’t achieved financial success either, and we instead derive emotional and other non-material rewards from our work. But many have internalized the idea of financial success, that they’ll be the ones to cash in on the ever present bootstrap canvas. The only difference between overly stylized “working class” rock bands of the 60s-80s, poverty-biting street artists of the 90s, mask wearing EDM DJs of the 2010s and contemporary social influencers is that now people can sell themselves directly to audiences without representation, live performance or even real content. None of this is that different from the philosophical issues with AI art, even if these ostensible artist-influencers are still people. I’m not saying we should be impoverished puritans. I’m just reminding us “there ain’t no money in the underground.” Maybe there shouldn’t be. Maybe we should just be able to sustain ourselves doing art, however we do it.

This douche shouldn’t be worth nearly $4 billion simply from coopting other people’s music, but I’m also pretty sure Paul McCartney shouldn’t be worth over a billion, either.

A medieval painting of a minstrel. While I’m not advocating for returning to this meta-patronage game, digital streaming has ensured most musicians make their livelihoods from gigs. It’s hard to imagine going back to artists making tons of cash.

I have no idea who these virtual influencers are but apparently they’re important. Hopefully including the copyright notice above prevents me from getting sued.

Then there’s the psychotic world of high end, curated art. AI will likely spur serious collectors to invest in complicated, mixed media work on canvas, as currency for human-made “authenticity.” It will certainly breed cottage industries differentiating AI-made pieces and prints from human-made work (ironically using AI). But the upscale art market also feeds on speculation, asset parking and money laundering, which were big contributors to the recent NFT crash (see my piece here). This could happen with AI artwork, too, creating a nonexistent asset bubble. Most AI generators already allow users to turn images into NFTs, thus recreating the enclosure central to early Capitalism. Only this time rather than fencing off common lands, they are transferring random, freely generated (or stolen) information out of the public sphere and into private markets. AI firms are tricking users plugging terms into a computer into paying a fee so they can call themselves an art trader. There’s nothing revolutionary about a further bifurcated market, particularly if it is alienating for most artists and pushes “authenticity” out of the reach for us all.

This is all because Capitalist commodification of art has long built expectations that the market can’t support. The current AI crisis is merely surfacing these rampant, existentially wrenching contradictions. It is forcing people who would rather spend their time in authentic creative pursuits into managing their brand identity to ever greater degrees, even as their original work brings less pay and meaning than ever before. It is instantly turning people who’ve forever wanted to channel the amazing ideas in their head from potentially aspiring artists into temporarily embarrassed auctioneers. I find it fascinating that the tools are simultaneously so empowering and so limiting, and that folks across the ideological spectrum are recognizing this, too. There seems to be a collective and growing belief that AI art could be so fucking cool, but the bitter knowledge that it won’t play out that way. Maybe AI will make us all into little artistic Antonio Gramscis, with our “pessimism of the intellect” and “optimism of the will.” But this again has more to do with economics than with technology.

Finally, there’s intellectual property. I’ve seen the “gotcha” type memes with zoomed in images of artists’ signatures on supposedly wholly original AI art. This is certainly happening, and it makes sense that successful artists are upset about others profiting off their creations or using them without attribution. But this happens all the time already, particularly if their work is high quality or original. The internet is riddled with websites selling poorly copied material for t-shirts, mugs, mouse pads or whatever. I buy some of that shit myself. But the majority of people selling plagiarized work barely make anything, while the third party websites they use rake in fees hand over fist. This is very likely how it will play out with AI, too, and I’m skeptical that it will be more emotionally or financially damaging for most working artists, who already don’t even know their work is being stolen. This doesn’t make it any less intense in a humanistic sense, but ultimately only compounds existing alienation. But it’s different than gridlocks in actually enforceable copyright, which is a potentially much more interesting shift.

One of many attempts using Disney content to highlight issues with AI and IP

Many are assuming that the IP world will remain hegemonic, AKA Mickey Mouse uber alles. But I’m not so sure.

By “actually enforceable” I mean intellectual property owned by the major firms with armies of copyright lawyers and algorithms at their disposal. These are likely to be the only ones with enough firepower to spot and act on the most obvious use of existing copyright in AI art, as noted by folks circulating recent parodied AI renditions of Mickey Mouse shooting guns, harming children, or doing other non-Mickey but totally Disney things. People sharing this stuff may be forgetting knock-off corporate imagery is already a global market, but they’re on the nose about one thing. The big firms have the financial and technological capacity to use AI to search for, identify, and threaten litigation against other AI “plagiarists.” One could even imagine a vast sea of Algorithmic stealing, enforcement threat and action that only rises to the level of human attention when cease and desist thresholds aren’t met. If it all sounds like it’s out of some dystopian 1980s William Gibson or Neil Stephenson novel, it probably is.

But this tension is another source of excitement, even liberation. It forces questions around the central notion of copyright that we should confront directly. Is intellectual property really worth anything? Should it exist? Indeed, can it exist in a world saturated with instant, high quality renditions of any idea anyone wants ever. I increasingly don’t believe it can, and that if it does in any fungible way, it must be relegated to the space of sharing and exchange around appreciation and equivalence, not for the sake of profit. There’s an important lesson in irony here that cuts deep to the core of libertarian tech fetishism, particularly as it relates to NFT and crypto markets. Sure, we could be facing the dawn of some kind of “post-trust” world dominated by instantaneous transactions and anonymity (somehow be free of fleecing, rug pulls and ponzi schemes). Or maybe it’s that the best thing currency has ever represented is a generalized sense of trust, and that the only way to move forward in a world saturated with AI art is to completely decommodify art and just trust the artist and process, human or not.

The only way to achieve a post-commodified art world is in a post-Capitalist world. This isn’t right around the corner. But the crises create opportunities for solidarity, organizing and short term policy change. We need a social safety net for artists that enables creation for the sake of creating, transforms technology from a threat to a tool, and allows us to fully develop our potential, through whatever means we choose. This requires support like guaranteed healthcare and housing, and potentially guaranteed income. It means bringing together artists and tools, encouraging learning and collaboration. It means moving away from profit as incentive and towards collective expression and aesthetics as incentive, as imagined in science fiction classics such as Ursula K. LeGuin’s the Dispossessed or Iain A. Banks Culture series. All of it must be predicated on solidarity, mutual aid and trust. If we achieve this, then creatives can share, improve and critique work without feeling alienated, without paranoia around plagiarism, expropriation, or cooptation. How can the best elements of human society thrive without trust, both in people and tools?

At the end of the day, it’s not about the tool, but the context and incentives surrounding the tool’s use. Hopefully creative AI is another force for ushering in the long-harkened era of fully automated luxury gay space communism, rather than some Disneyfied AI lawsuit-cum World War III constitutional robocracy hellscape. This is unresolved. In the meantime, may we all enjoy our newfound powers of getting AI to combine all manner of divergent material in new, glorious and stupid ways. It will certainly be interesting to see how all the first truly sentient AIs feel about all the trash we had their predecessors create. But I’ll save those thoughts for later.

For now, enjoy these MidJourney images based on the prompt “Antonio Gramsci eating Mark Fisher’s Ghost.” Apparently the AI’s don’t know who Fisher is.