Twitter’s Techflation Test

The shitstorm surrounding Elon Musk’s belligerent takeover of Twitter and subsequent “Twitter Blue” debacle is devolving so quickly that it doesn’t lend itself to thoughtful analysis. The service’s launch, satirical takedowns, stock crashes, layoffs and rebranding have flown by, along with pithy proclamations ranging from celebrity and organization boycotts, to former staff claiming two-factor authentication failed, to Musk stating Twitter was more popular than ever and a majority of 15 million concurrent users voted to reinstate Donald Trump’s account. It’s all vaguely incoherent, legitimately terrifying for some users and many staff, and globally mockable. So it’s basically just an amplified version of Musk’s everyday life. But it’s also an indicator of tech industry chaos, a harbinger of cuts to come, and an exemplar of inflationary crises under the mad logic of Capitalism.

Most media commentary has been around how Musk’s delusional communication and leadership styles create vulnerabilities, whether in Twitter or throughout the investment market. This makes sense, given Twitter’s increasingly asinine portrayal as the public sphere, Musk’s obsession with free speech uber alles, or random kids tanking Ely Lilly stock by billions using an obviously spoofed profile claiming insulin is free now.

I’ve never used my Twitter account, and even I wanted to revel in the takedowns of organizations like AIPAC loving apartheid, Chiquita overthrowing the government of Brazil, or BP admitting they’re killing the planet. But while these tweets ironically get more attention, they pale in comparison to the material impacts of Musk’s layoffs and the cuts he’s legitimating for similarly overvalued competitors, most of whom followed the same paper thin yet bloated growth models.

The Tweet that tanked a global corporation for billions

But no one abandoned BP for being “eco-apologist”

It’s really funny and based on historical precedence, but…

… what’s really going on is way worse.

Social media and tech firms will spend the coming days closely monitoring Twitter’s stock valuation, user engagement and ad revenue to estimate how extreme they can be with their own cuts. If Twitter doesn’t totally implode, others will trample their workforces with mass layoffs and transitioning to brutally long workweeks. They’ll demonstrate that the truly terrifying nature of Musk’s rhetoric is at the level of the market, not his personal actions. A few executives may even adopt his near psychotic language bordering on open class warfare to legitimize the proletarianization of their workers. But many more will go the Mark Zuckerburg route. They’ll publicly lament having to cut while privately relieved that Musk’s extreme rhetoric makes their own layoffs less horrific, even sanguine. Some may feel genuine remorse. But the smart ones have seen this coming for a long time and are prepared to absorb it.

This is already the case throughout the tech world, but this is just the first round and it won’t stop there. Facebook followed twitter immediately, laying off 11,000 workers (13 percent of its workforce). Amazon cut 10,000 and is setting up for more. Just before Thanksgiving, a dear friend subcontracting at Google said something like “it’s only the truly evil firms that are doing it. Google isn’t planning layoffs.” The next day, Google announced a plan to identify and cut 10,000 “poor performers”. All of this was terrifyingly before Black Friday and the holiday shopping season, when firms are supposed to finally be profitable for the year. What happens throughout the economy in the coming weeks will be as much determined by tech workforce adjustments as it is by consumer confidence and media representations of inflation. The recent upsurge in labor militancy may stave off the worst in some sectors. But cuts and a crash are coming.

There are several underlying logics of Capitalism contributing to our crisis. But two require special attention- speculation and growth expectations. Musk is the modern personification of both speculation and stock overvaluation, whether through crypto Ponzi schemes or driving Tesla’s market Cap to over $1 trillion, even as there are more Teslas in recall than in production. But the global crypto crash shows he is not alone in this seemingly new moment, which is ironically driven by the same economics we’ve faced throughout Capitalist history. This speculation / growth intersection contributes to all bubbles and crashes, going back at least to the 1600s Dutch “tulip bulb” crisis. It precipitated the Great Depression, drove currency crashes in the 1980s-90s, and was at the center of the 2008 housing-induced financial crash. The only substantial differences this time are that technology merely accelerates boom/bust cycles, the last collapse was quite recent, and it was followed by global working class upsurges and a pandemic that are fresh in our minds and Twitter feeds.

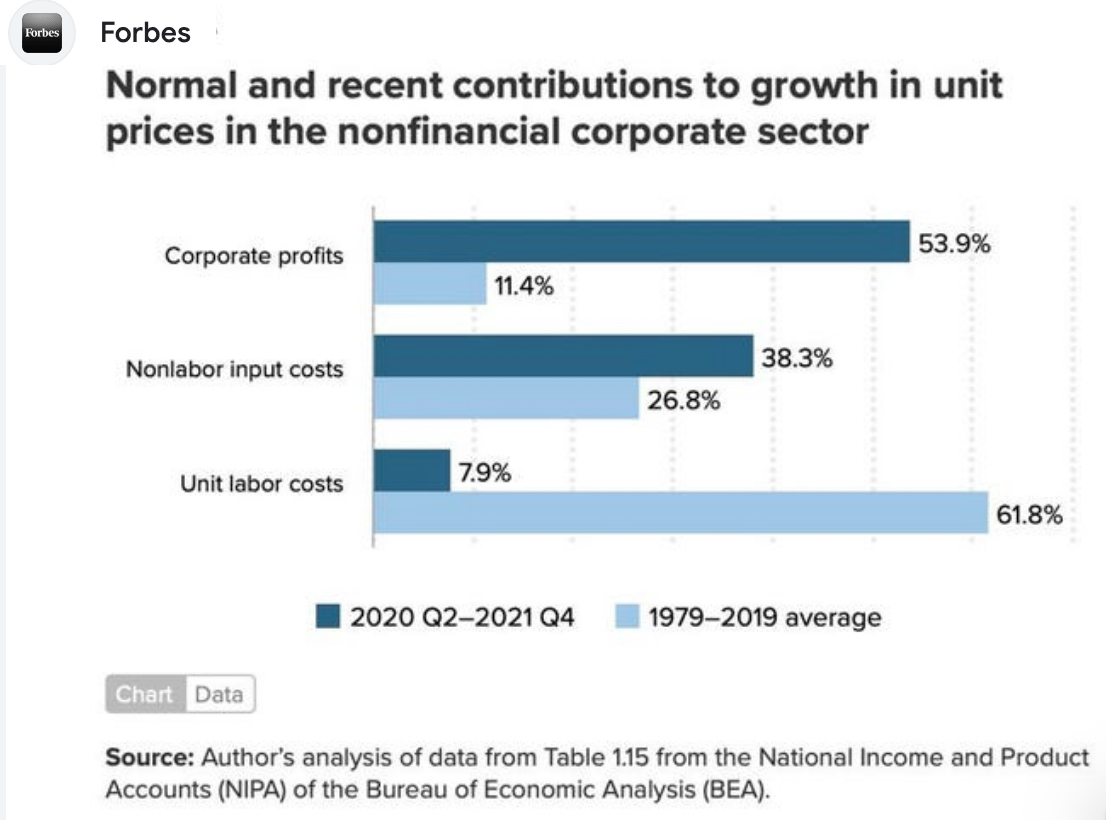

As always, Employers and the mainstream press will blame inflation on wages and crashes on underconsumption or market “adjustments”, rather than underlying economic structures. But the unequal post-pandemic recovery is ripping apart common narratives. Working folks are realizing corporate profits and Capitalist growth expectations are really what’s at issue, and they’re reminded every day in the grocery store line or at the gas station.

Sure, grocery workers got limited hazard pay from the pandemic and countless workers have “quietly quit,” left for better positions, or refused to take substandard jobs, driving up wages. But it’s common knowledge that grocery chains such as Kroger, Wal-Mart and Fred Meyer are still making record pandemic-induced profits. Just as it’s common knowledge that companies such as Amazon, Zoom and online education providers adjusted to the demand generated by early COVID lockdowns. More demand always means more profit opportunities. Firms know this. Investors know this. The market requires this.

Grocery chains literally reversed the primary driver of inflation from wages to profit, during their highest profit period ever.

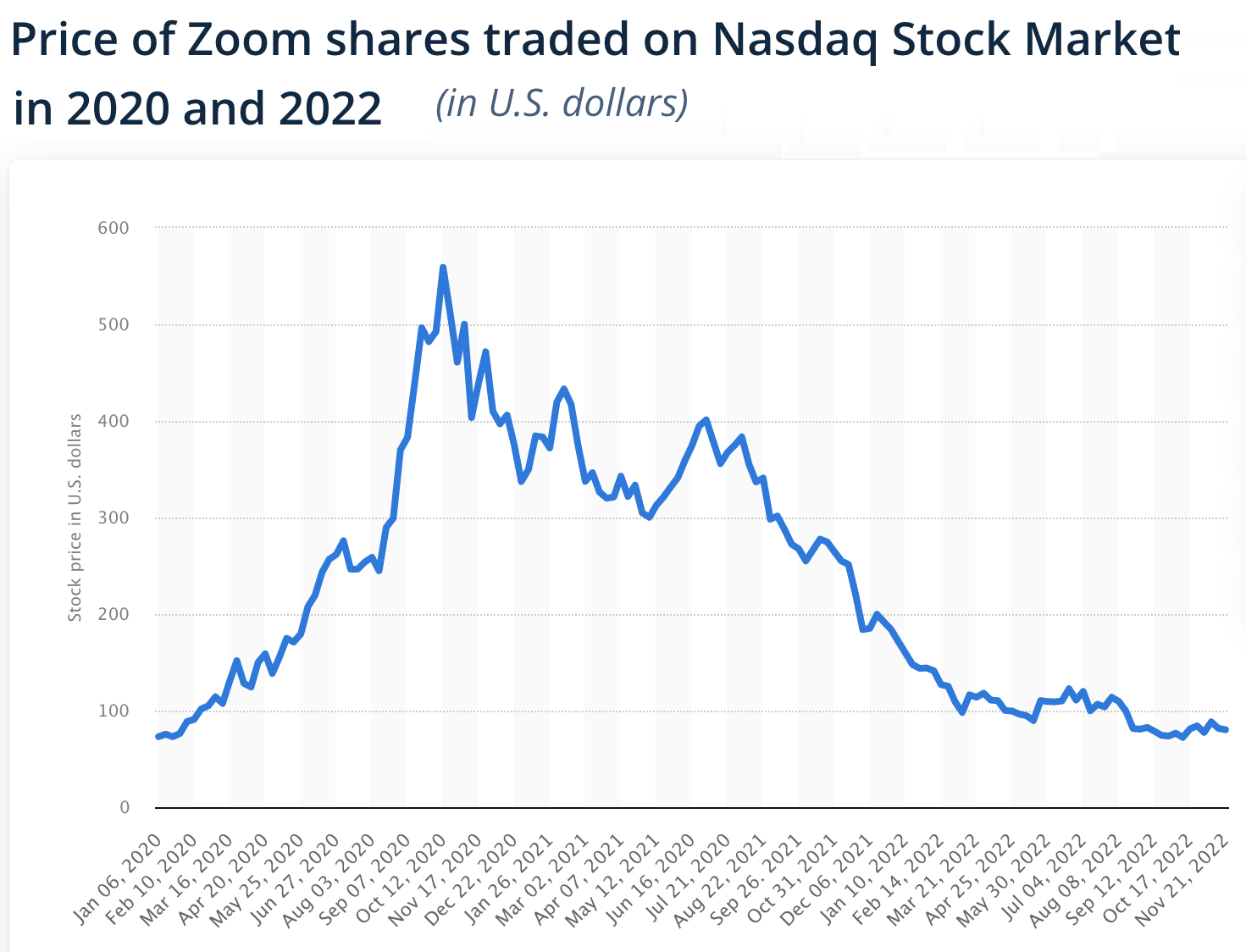

Zoom go up. Zoom go down.

Greater demand inevitably meant tech staffing expansions. Believe it or not, we still haven’t reached the singularity, and the algorithms do not do all of the work at these places yet. Firms had to address immediate and projected staffing needs, along with projected profits. Twitter brought on over 3,000 new jobs between 2020-22, streaming giant Netflix brought on 3,000 (20 percent growth), and Facebook over 30,000 (60 percent growth), even as other firms were laying off. Of course, Facebook’s was coupled with the disastrous launch of their “Meh-Ta” parent company (read more here). But they still collected ad revenue hand over fist, just as streaming services collected subscribers and consumers collected random, drunken or depressedly purchased consumer goods and our fair share of COVID weight. In the case of big tech, this COVID weight came via bigger payrolls and massively bloated, unrealistic profits.

Capitalism incentivizes firms to be competitive in the market and maximize profits. The most universal way to achieve both is to sell as much of a product as possible at the cheapest price possible, undercutting competitors. As any good lefty or pro market economist knows, labor is the most variable production cost, meaning that it is easier to maximize profits by extending hours or firing workers than it is by selling land or spending less on equipment. There are many well-known inherent contradictions around this tension at the heart of Capitalism. Something less wonky or left-minded folks often miss is that once a firm achieves a certain profit margin, it creates expectations for owners and investors around future profits. This is not only the amount of profit, but the rate of profit and the rate of growth. The market logic dominates all. But what happens when this logic confronts a novel, temporary social situation, such as a global pandemic induced spike in specific behaviors?

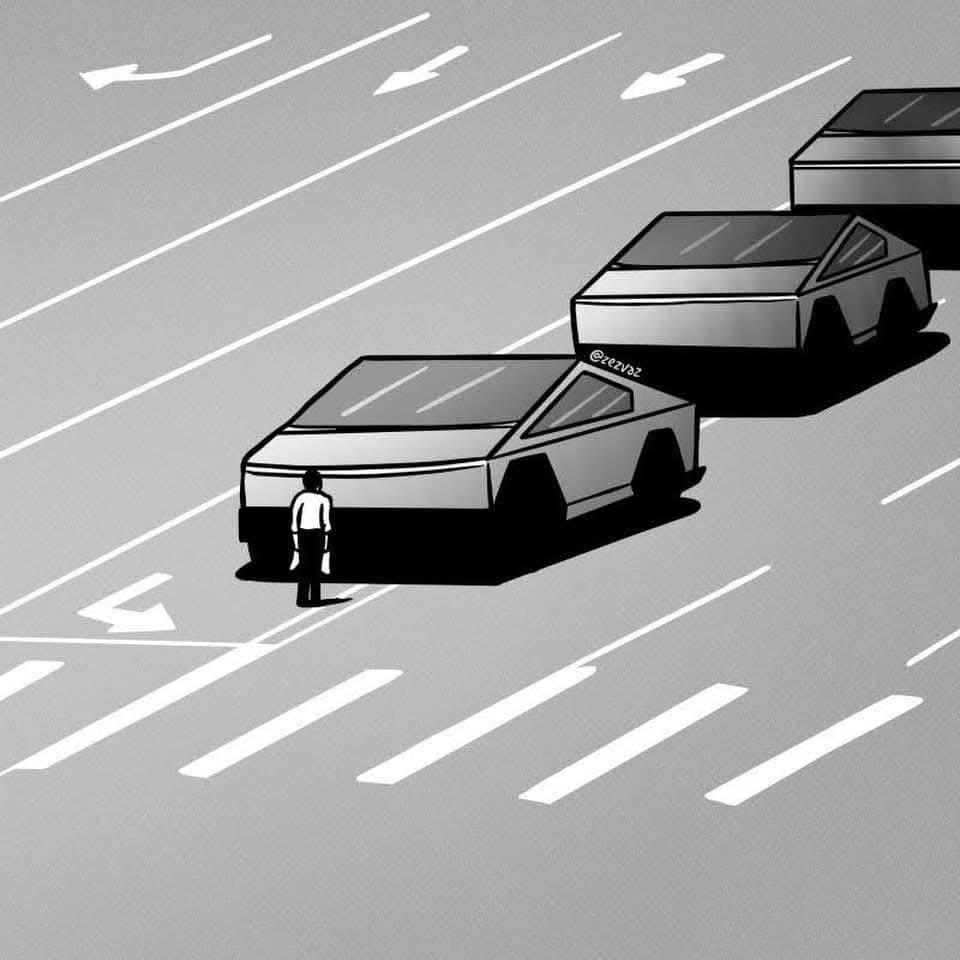

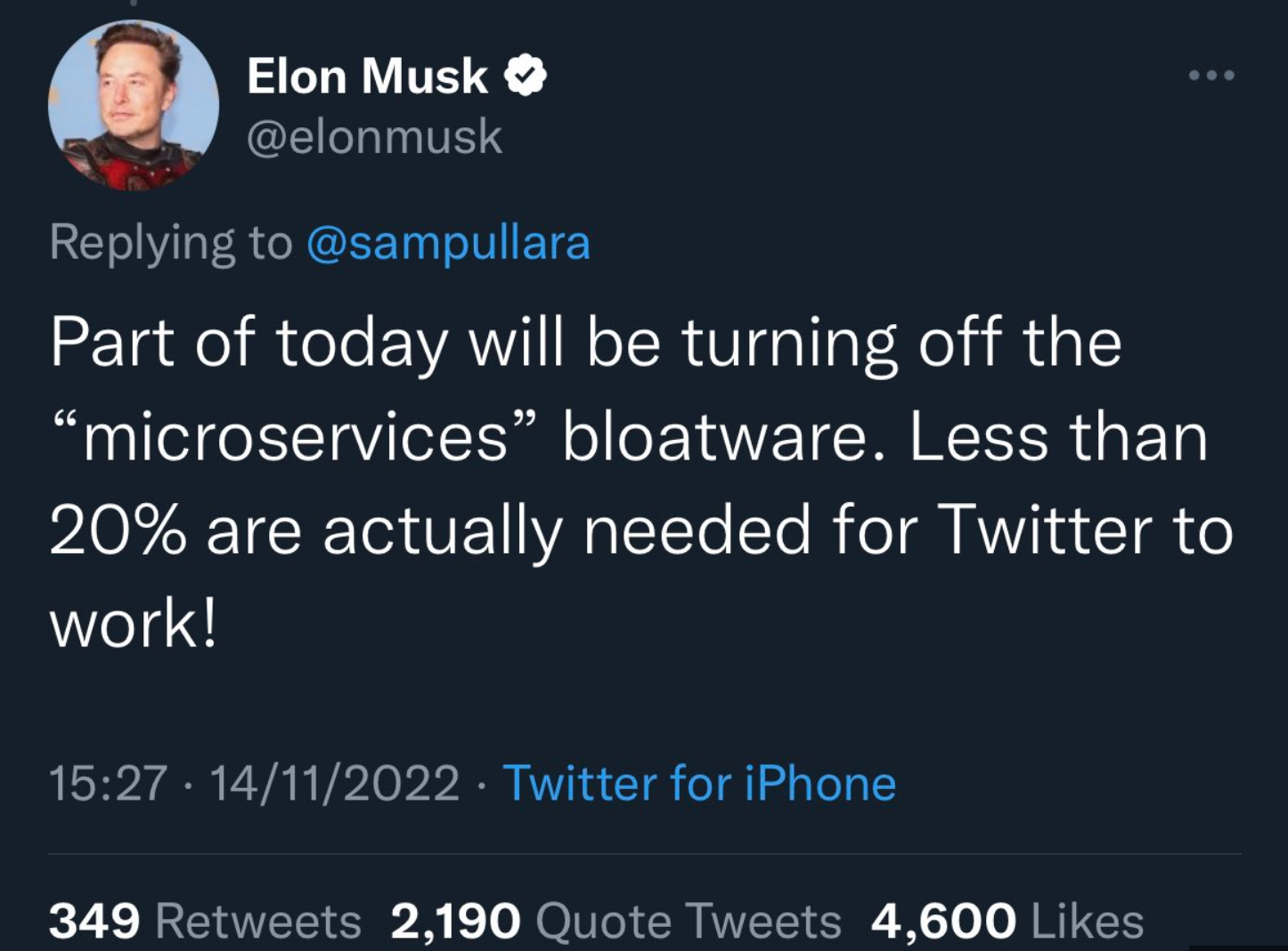

Grocery chains are thus expected to maintain the same rate of scarcity, supply chain and paranoia-derived profit even as the pandemic “fades.” Bloated Tech firms have to reckon with people spending marginally less time online after returning to in-person work or their few consumer activities that survived the pandemic unscathed. Firms have to maintain this profit through layoffs, extended work weeks, and reduced benefits and wages. In the end, it’s about greater productivity for lower expenditures. Automation remains a constant and occasionally valid threat, but even in the highest echelons of the tech world it’s always been people producing widgets. That’s why Musk was so quick to lay off so many and issue such public ultimatums about work hours. That’s why tech CEOs who ostensibly hate him are secretly jealous and waiting to drop their own axes. They don’t care if their “micro services” temporarily break if they can weather the storm without hemorrhaging users.

One of the many ways Musk is setting the tone. And you thought airline cuts to services were bad?

Basically every Capitalist every time there’s a tight labor market or a strong union movement.

I’m not saying things like “corporate greed drives everything wrong with our world” or “the wage-price spiral doesn’t exist.” These are simply factors of how markets work under Capitalism and happen regardless of who’s in the driver’s seat. Tech firms strove for profit, took on extra workers, and overproduced knowing that the market would punish them if they didn’t. Just as they know the market will punish them for not streamlining now. And millions of workers spending money from their small raises does drive up prices more than hundreds of executives and investors hoarding billions in new wealth. But hedging on profits is what keeps prices high. The biggest firms and entire sectors are reveling in the narrow space where everyone price gouges. Sure, they want to undercut competition, but no one wants to be the sucker who exits early during a boom. Even with a war threatening the world’s breadbasket and oil cauldron. This is the boom/bust cycle of Capitalism and it contributes to inevitable crisis and collapse… over and over again.

The other under-discussed force at play is the proletarianization of skilled labor. The profit drive incentivizes firms to seek a larger labor supply and to deskill work, whether via automation, weakened labor laws, or outright brutality. For big tech, this generally occurs through creating a global, educated but cheap labor force at all levels of the industry. Emergent improvements in Artificial Intelligence are also finally reducing the need for some low-level coding jobs, while expanding demand for low pay bug testing. Prior to the pandemic, I imagined the future of this tech work in coder cubicle farms. Now I’m seeing it as more of a fully remote Mechanical Turk-like gig economy. Regardless of where it resides, it will suck if it’s anything like the tech industry’s treatment of existing low wage workers. You know, the folks organizing apple stores, throwing themselves out of windows after days-long shifts at the FoxConn plant, or resisting Musk-backed coups against democratically elected indigenous leaders in Bolivia.

But contradictions abound, and proletarianization ensures class consciousness and struggle continually rear their lovely, not-so-little heads. The brilliant and recently passed socialist Barbara Eherenreich coined the term “Professional Managerial Class” in the 1970s. She included all manner of mid-level management and white collar workers in this group. She saw the PMC as a buffer, one of several forces saving Capitalism from Capitalism. But she also noticed the potential for proletarianization and wrote about it later, emphasizing this possibility with clerical workers, teachers, nurses, reporters and government workers. These overeducated but increasingly underpaid workers have been at the center of struggles, organizing drives and strikes over the last decades. Teachers and nurses drove the largest recent job actions, and 48,000 academic student employees throughout the University of California system are in an open-ended strike as I write.

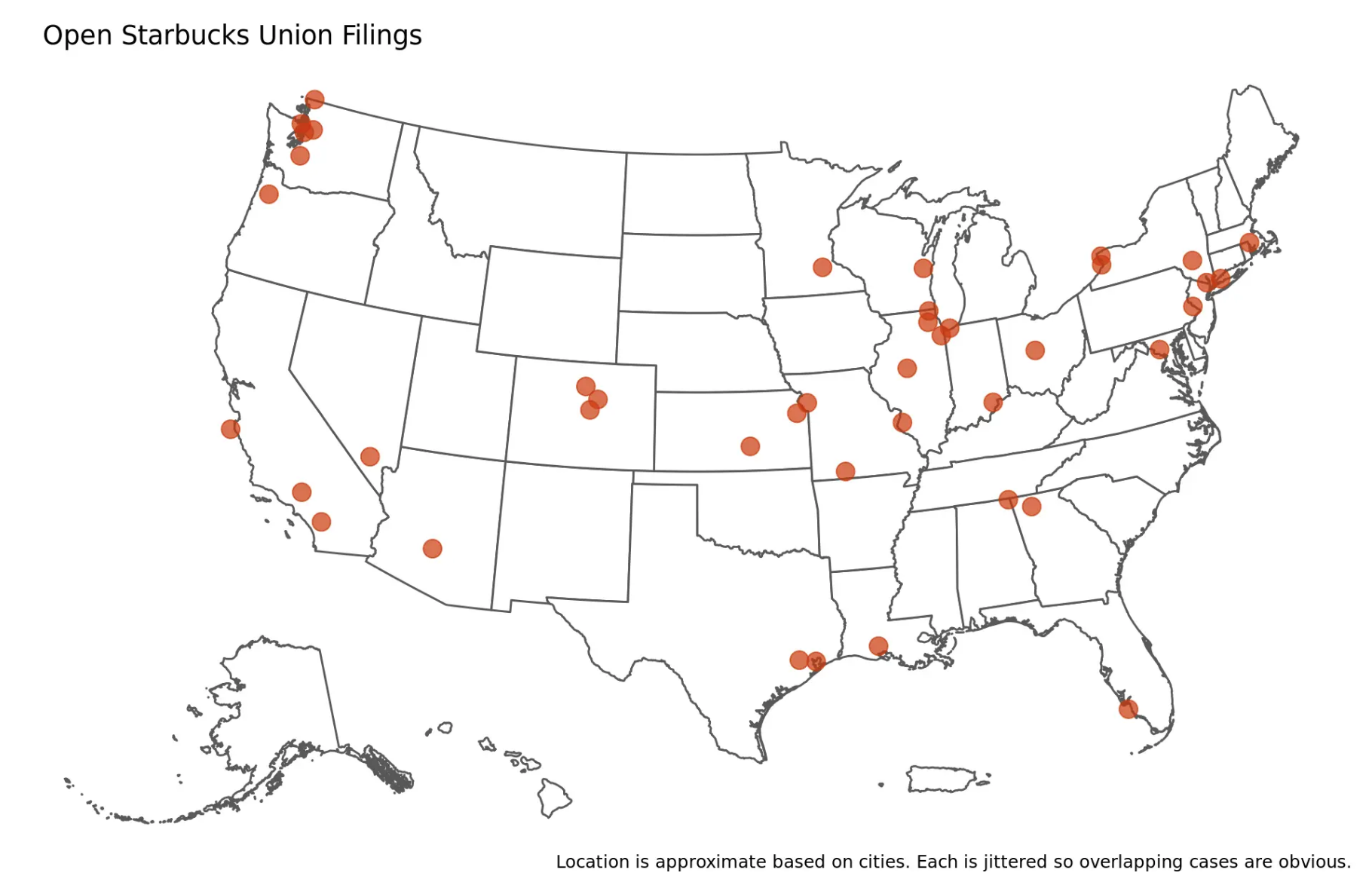

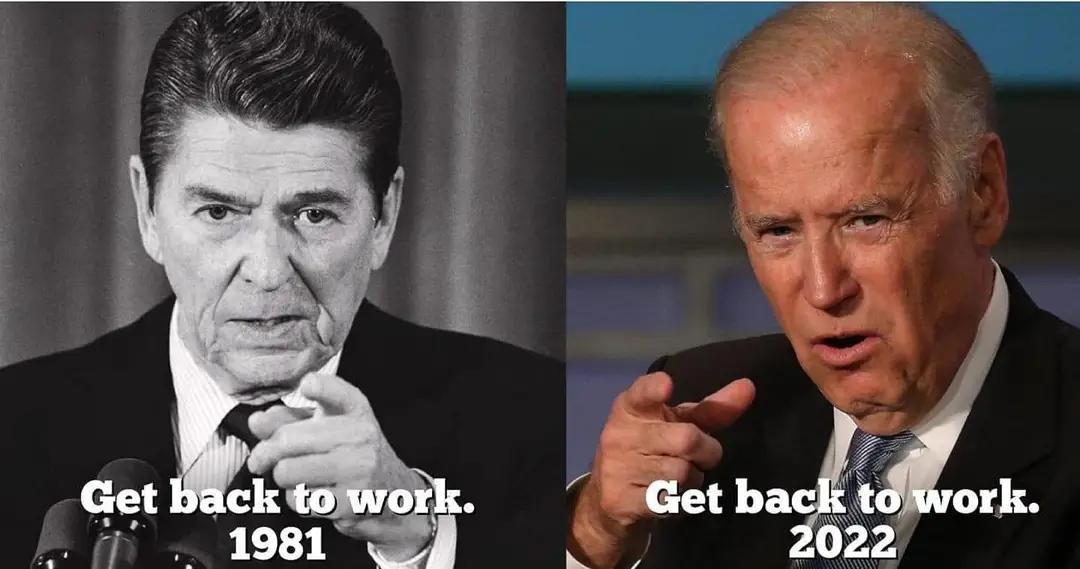

I don’t want to overstate the role of white collar workers in the labor movement, or the inevitability of mass militancy, particularly in high tech. There have been just as powerful recent actions by blue collar workers, such as the 10,000+ member United Auto Worker strike against John Deere, thousands of workers striking Kellogs across the country, huge Starbucks and Amazon warehouse wins, and more. But while the fuse is primed, some of the key political conditions aren’t there. While I was writing this, the Biden administration pressured Congress -including progressives and three of four elected DSA members- to avert a coming rail worker strike over simple demands for paid sick leave. It’s one thing to be a class in itself and another to be a class for itself. This is likely more so for educated, high pay tech workers who see themselves as connecting to politics more around values and identity than material needs.

Close to 400 Starbucks stores have tried to unionize, with over 250 stores representing almost 7,000 workers voting yes so far.

Despite this moment, Joe Biden is doing his best to impersonate Reagan’s breaking of the PATCO strike… except, you know, as a Democrat during an unprecedented labor surge.

So what is to be done? First, big tech needs to get organized, pronto. There have been inroads with Amazon and with Google’s “Alphabet Workers Union”, with successful job actions around gender pay equity, contracting with dictatorships, trans worker rights and more. Most actions were driven by pro union folks surreptitiously radicalizing their colleagues. This has recently evolved along more traditional union organizing lines, partially inspired by victories by Amazon warehouse workers, Starbucks barista and other “unorganizable” workers. Tech workers are identifying as much more working class every day. Just as workers everywhere are developing much more class consciousness. It’s always better to organize when you have more structural and bargaining power, which they clearly lack, so the future is unclear. This is why the government betrayal of rail workers is so devastating and why things might not be so pretty in tech. But this looming interregnum is a time of monsters, so who knows?

We also need to shift the narrative on inflation. This will be hard, given that it’s a “liberal” one repeated constantly in the press. A couple months ago, I heard a maddening NPR piece about grocery prices in Seattle that blamed the city’s hazard pay ordinance, union workers and supply chains while never mentioning profits. I’m not saying everyone should call into their least favorite local NPR station offering corrections. But the left needs to be tighter in our messaging and dispel internalized arguments centering workers and consumption whenever possible. Like all good organizing, this requires open-ended questions about what people think causes inflation, what it’s like having to spend more, and who ultimately benefits at the end. Deep inside, workers know it’s not themselves, government service users, or rail workers looking for sick days raking in profits. And they all feel the pain of more expensive food, rent, credit card payments and higher interest rates.

FInally, the public sphere can’t be a commodity. This includes whatever tool we ultimately land on for pithy online communication if we ever want truly free speech or participatory democracy. Elon Musk hypocritically identifies as a “free speech maximalist.” His deranged vision is akin to the Citizens United decision of the Roberts Supreme Court, which ruled that unlimited corporate spending on elections was somehow equivalent to individual speech. But real free speech and democracy are hard, time consuming and antithetical to the profit motive. Sure, people with differentiated views and power will always try to manipulate each other. But this is different from the entire experience being mediated by a for profit firm, in this case one with an increasingly right-wing and demagogic leader. The internet has to be a public utility, and there needs to be at least one significant social media community utility. So, yeah, nationalize utilities. Nationalize Twitter. Nationalize railways. Then maybe tech workers will thrive, along with renters, small business owners and the rest of us.

One concept I return to repeatedly is the notion that Capitalism breeds democracy. I believe this is true, but only because the exploitative conditions of Capitalism force people to come together to change them. In Capitalism’s earliest phases, this was through enclosure, the world’s first mass homeless problems, and centralizing countless people into tight quarters under oppressive working and living conditions. This is where modern participatory democracy emerged, generally through labor movements and socialist parties. Maybe there can be a modern analog to this in late stage Capitalism, where the tools of online oppression are liberated both for the people working on them and being worked on by them. I’m not sure of the path forward, but I do think the tech worker class consciousness and mass rejection of the insane logic of inflationary Capitalism are necessary but not sufficient conditions. The social conditions of this moment are vastly different from the last several booms and crashes. We remember differently. We feel differently. We engage differently. Maybe we’ll organize differently.

Here’s hoping.