A Mehtaverse of Cryptocrats

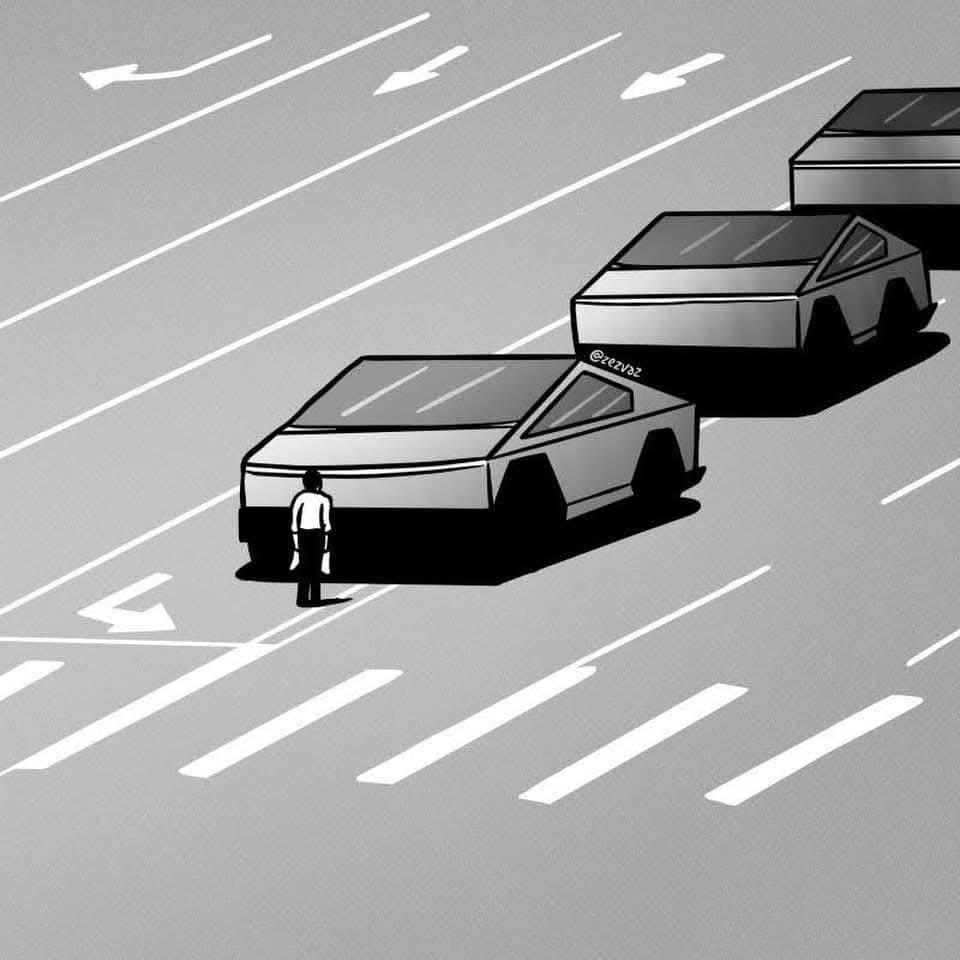

Mark Zuckerburg seemingly expected his Metaverse launch to be the digital shot heard around the world; the actualization of the avatar space long-heralded by cyberpunks, futurists and campy science fiction. So why did countless Facebook users, media outlets and the market react with a collective groan? And why did this groan turn to a whimper when everyone’s favorite libertarian narcissist, Elon Musk, bought the largest interest in Twitter to ostensibly protect his free speech? After years of scandalous data extraction, monetizing all aspects of attention, and market shattering social media belligerence, people saw both as ugly from top to bottom. And I’m not just talking about Metaverse graphics and 4am Musk tweets. Zuckerberg quashed what lingering hopes many had for a digital public sphere, and Musk just reminded the whole world that his free speech is worth more than theirs.

Both events have huge implications for markets and for political organizing. Zuckerberg’s utopia has already turned into a volatile, overly financialized sinkhole that lost 26 percent of its value in one day, with reverberations throughout the “digital real estate market” (whatever that is). Musk’s Twitter investment almost certainly allows him to avoid censorship, not only from Twitter itself, but the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) and other regulators trying to rein in his stock and cryptocurrency value-driving rants. Both will drive expansion of cryptocurrency and digital financialization without frameworks to protect individuals and institutions from their impacts, just as new markets and profit opportunities grow exponentially. Both stifle political dissent and create “path dependency,” ensuring that even the most democratically-minded competitors will follow suit.

Most Zuckerberg critiques I’ve seen revolve around his roll-out, low consumer trust, or the poor “Meh”-taverse user experience so far (full disclosure: I haven’t tried it and I’ve only used Virtual Reality a few times, so I’m an unreliable narrator). Musk is either psychotic or brilliant and unknowable, depending on who you ask. But cultural critiques didn’t cause the Meta crash. It was driven by Apple’s new privacy systems for IOS that drove down their bottom line. This combination of popular disinterest with crushing competition would be the death of a small firm.

Of course, Zuckerbot’s early adoption and market share combined with our shortening attention spans means we’ll probably all use Meta2.0 or some equally innane shit soon. The economic Twitter fallout has yet to come, although may it be spared given Musk isn’t joining the board… for now. And I wouldn’t at all be surprised when Twitter launches something like “TweetOrbit,” or if Musk affectionately dubs it the “Twatterverse” when running a fire sale.

Bot’s gonna bot

The bigger issue -and one that’s not receiving enough mainstream attention- is that both are trying to define the norms of a new speculative financial market based in cryptocurrency and digital real estate. After failing at their own crypto twice, Facebook decided to jump the shark and instead go all in on dominating the digital space in which shitty Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) are displayed, normalized and gamified. After facing regulations and roadblocks, Musk decided to circumvent them all. They are at once wallowing in the contradictions of the current financial order while trying to birth a new one based on the same faulty logic. It’s the tragedy of the digital commons and a comedy of eras with incredibly dangerous potential. But at the end of the day, even with all this gloss, it’s just the same old shit. Want proof? Just look at the last 100 years of financial markets under Capitalism.

The Logic of Accumulation

Karl Marx predicted that the contradictions at the center of Capitalist accumulation would lead to its demise. The insatiable need for profit and growth had an inherent tension with scarce natural resources, the limits of national economies, and the dwindling buying power of workers constantly squeezed for more productivity and lower wages in order for Capitalism to survive. The Capitalist mode of production was inherently exploitative. The relations of production between the owning class and the working class -with all of their immiseration- created the conditions for revolutionary change and a new economic order. Early Socialists of all stripes (along with more mainstream economists) predicted that Capitalism was fundamentally unsustainable. Many foresaw it ending in their own lifetimes, potentially at their own hands. Folks on all sides believed this, and it was in no small part a contributor to World War One.

Brilliant and radical “Red Rosa” basically predicted all of this

Elon Musk makes predictions, too

It took decades of late colonialism, early globalization and financial crises to shake this belief and create theories on what drove Capitalism’s zombie-like survival. The brilliant and still relevant Rosa Luxembourg made some of the greatest contributions. She suggested imperialism, colonialism and war provided mechanisms for expansion and accumulation. As long as there were non-Capitalist locations and economies, there was room for expansion. As long as there was war to be made, there were justifications for massive increases in production (and ideological tools for whipping the working class into shape, such as nationalism- the gambit that Vladimir Putin just made and is failing miserably to fulfill). This may seem common sense to some today, but it was revolutionary. It informed Luxembourg’s resistance to Germany entering World War one, even as Socialists everywhere lined up to support national agendas. It ultimately led to her murder by the German State, in which her own political party was complicit.

This exegesis is woefully insufficient for capturing these contributions, but it’s important context. Scholars have long recognized that the creation of new markets is an essential aspect of Capitalist survival. It became crystal clear with currency markets in the 1950s-70s era of decolonization and the collapse of the “Bretton-Woods” model. The gold standard ended, the International Monetary Fund’s “Structural Adjustment Programs” were born, and recently liberated countries were disciplined into paying post-colonial “sovereign debt.” It was the birth of Neoliberalism, which exploded under Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and proxies such as Chilean fascist Augustus Pinochet. It led to rapid financialization of vast swaths of the economy and exploding consumer debt. It brought decades of currency speculation, interest rate manipulation, ridiculously financial instruments such as “swaptions”, and tranched securitization of bad debt. You know… all the driving forces behind the 2008 financial collapse.

You don’t need to know concepts here to realize that it sucked for working people everywhere, whether it was through having their unions or pensions gutted, paying more for social services, exploding credit card debt and bank foreclosure on their dream homes, or being imprisoned or murdered for speaking out. While having an analysis helps (and there’s lots of theory you can read), what matters are the simple understandings that elite economic interest drives this, Capitalism requires constant growth, and financial markets are inherently speculative. In an ironic twist, the very regulation of these markets leads to the emergence of new ones. This is how many of the most ridiculously named financial instruments sprang into being. Rosa Luxembourg would be rolling in her grave, if that’s even her body. This is precisely why her debate between reform and transformation (or revolution, or whatever) is still relevant.

These new digital markets are a Hail Mary by a technocratic portion of the global elite to create a potentially limitless zone of Capitalist accumulation, starting with the things they know how best to exploit, speculative financial markets and real estate. Just like with bitcoin and NFTs, the early adopters have a deep incentive to frame it as something else. And, while this is entirely my own “speculation” verging on conspiracy theory (which I normally hate), I’m guessing it was launched preemptively, precisely during the later stages of a pandemic, in order to try to prop up a new market and reschedule the next collapse. Generally, the ruling class would be incentivized to wait, as there’s still a lot more blood to squeeze from the real economy turnip. The only other reason it would look, feel and function so shittily is because the ruling class are also incentivized to do everything as cheaply as possible. Oh, wait. Occam’s Razor. Maybe it sucks because all Zuckerbot, Musky and co care about is profit? Meh.

I feel obligated to defend against a pro-crypto response here. Some folks are reading this and thinking something like “the whole point of crypto is scarcity. How can you be critiquing a limitlessly expanding market when things will run out, which is what makes line go up, bruh?” Many thoughtful and often pedantic lefties have spent their whole lives studying this contradiction between rampant expansion and imposed scarcity. The fact that there is ultimately limited bitcoin isn’t that different from corporate farms dumping milk or burning wheat when prices get too low. And it’s rendered meaningless when there are constantly new cryptocurrencies or NFTs emerging. Every. Day. The greatest “whales” and “hodlers” are secretly speculating in massive amounts, even as you lose your last paycheck. And, no, the post-trust scarcity of crypto is not going to end war. It’s much more likely to start wars. Elon Musk is a ponzi scheme.

It didn’t have to be this way

Want proof? Check out the most newsworthy events over the first few months of the Meh-taverse. It was all digital space and NFT speculation, including nonexistent real estate selling for tens of millions of dollars, based on the prediction that there will be a trillions of dollars market capitalization in a few years. Cryptobro speculators now have places to hang up their shitty NFT JPEG art and hustle it off to their friends. The closest approximations of a public sphere have been shitty digital concerts and raves, often including casinoized contests to “find the NFT.” Yup, the first public facing events are multi-level-marketing schemes disguised as boring parties with terrible EDM. It’s hard to overstate how much this enrages me. It unchecks my boxes for a commitment to the public sphere, my belief in the potentially liberating role of technology, and my love of cyberpunk, science fiction and underground music. It fucking sucks, and not because I’m a luddite. It just doesn’t have to be this way.

How’s Jack Dorsey first tweet doing now? Oh, right… the guy who bought it for almost $3 million tried selling for $48 million and got $298. It’s worth literally nothing. Crypto-hustler Sina Estavi’s net worth just plummeted from about $15 million to about $12 million. Still $12 million more than mine.

There have always been competing artistic and political visions of our digital future. Most have been within the framework of Capitalism, either as naively utopian beliefs about technology and market competition liberating mankind, or the more frequent -and so far accurate- dystopian portrayals in science fiction and art. The utopians follow the footsteps of folks like Ray Kurzweil, who brought the concept of the Singularity, the Steves (Wozniak and Jobs), or early crypto-activists responding to the 2008 crash. They all shared a belief in a revolutionary break with the old, driven by things like artificial intelligence, post-humanism or democratizing finance. The best versions imply technological change will render Capitalism obsolete, that it won’t be sustainable as we move from scarcity to abundance. There is a broad spectrum of beliefs here and I’m being reductivist lumping them together. But they share a common feature. The future they predicted has yet to come to fruition, and their reasons for why it hasn’t are spurious at best.

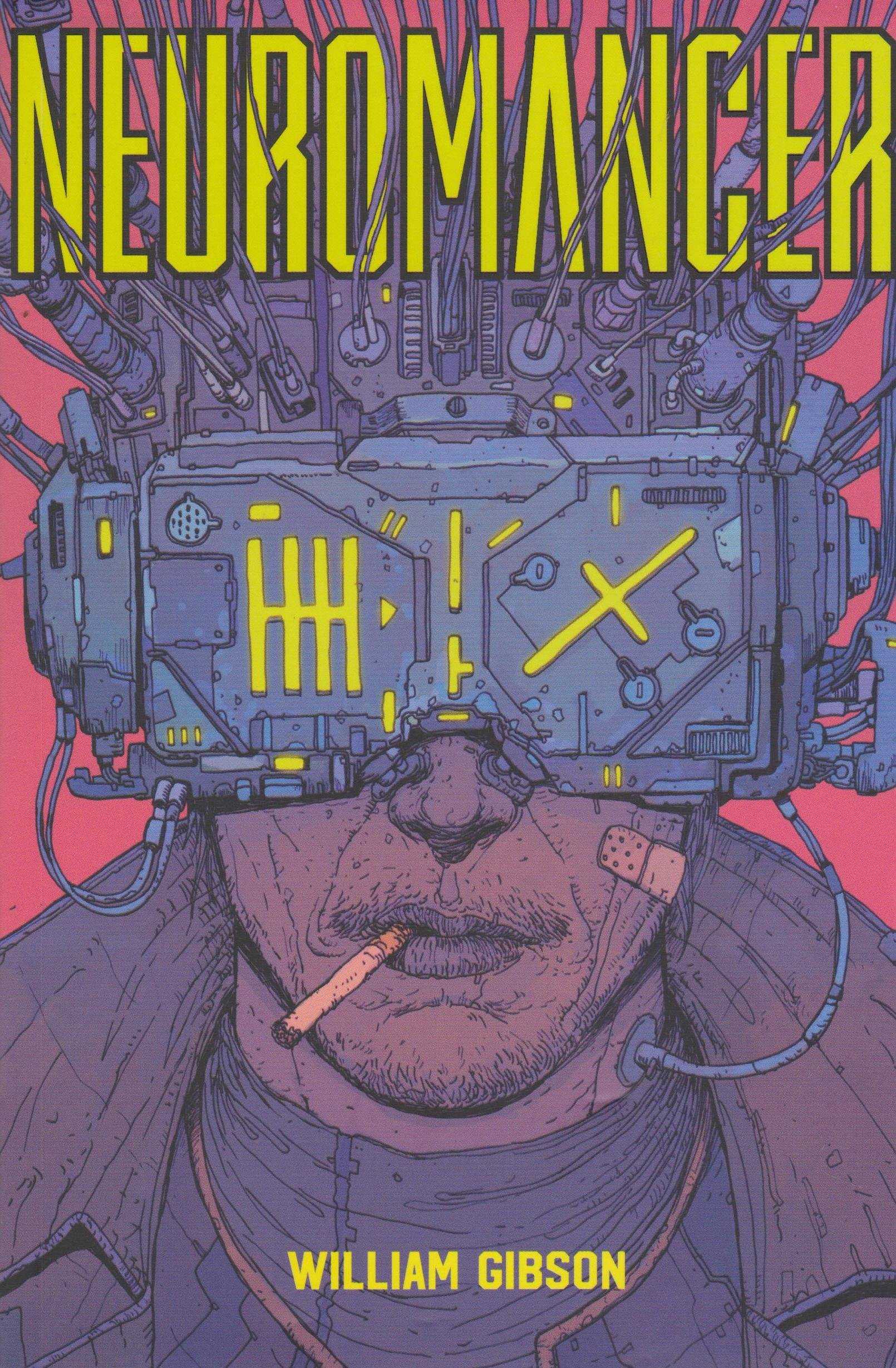

The dystopians have been more accurate, if a little too generous on how far technology would progress by now. Some of my own biggest influences as a young person included works like Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (Blade Runner), William Gibson’s Neuromancer or Neil Stephenson’s Snowcrash. Gibson first popularized the concept of a “Matrix” as a shared cyberspace and Stephenson first used “avatar” in the digital context. All of them shared paranoia about what technology would do to society, critiques of economic inequality, and noir-inspired beliefs in anti-heroes (in Snowcrash literally referred to as Hero Protagonist). They foresaw mass poverty, pestilence and contradictions in social access, surveillance, and the notion of what it is to be human. They, too, were quite different from each other. Dick fell into paranoia, believing aliens were trying to communicate with him. He died of a drug-induced stroke, fulfilling his own visions from “A Scanner Darkly.” Gibson moved onto sublime, realist speculative fiction. Stephenson became a pedantic narcissist Libertarian.

Books like William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Neil Stephenson’s Snowcrash nailed a fair amount of dystopian future, albeit with worlds a bit more advanced than we actually are

What these seemingly oppositional views hold in common is the framework of Capitalism and a belief in the role of technology as simultaneously outside of the framework but embedded within it. This sets up the current situation as inevitable and technology as the only means of escaping it. Just as Zuckerburg does. Just as most embracings and critiques of the Meh-taverse do. They reinforce the essence of Mark Fisher’s “Capitalist Realism” and the belief that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than it is the end of Capitalism. They deemphasize the economic and material base of oppression, and the fact that technology is a neutral tool used both for oppression and liberation. While they have a ton of imagination about the good and bad that emerges in these spaces, they pay little attention to how social agency and political organizing can overcome it. This may be just because all stories need heroes (or antiheroes), and I’ve found myself in this same trap with much of my own writing. But this, too, is precisely because the market moderates how we perceive ideas of oppression and liberation.

Of course, there are whole sub-genres of science fiction that buck this trend and present more visionary futures. Writers such as Kim Stanely Robinson, Iain M, Banks, and much Afro-Futurism tackle what Socialism in space looks like. There are academics and activists who’ve wrestled with it forever, too, some with compelling and scalable ideas. But that’s not the point of this piece and most take the liberty of writing about after whatever needs to change has changed, rather than how we’re going to change it. Let’s say we do want a democratic, universal virtual commons. Is it possible to create in an egalitarian way that includes a robust public sphere, less inequality, and less speculation? Could it allow for people to “consume” digital activities, services and assets without creating environmental devastation (whether via fast fashion and consumer goods or crytpo-mining energy consumption)? Could it provide creature comforts without a tragedy of the commons? Could it contribute to democratic participation in the polity and an engaged community of netizens, or whatever?

I think it could. But this happens through political and community choices, not technology alone and certainly not via the market. Sure, the infrastructure and capacity has to exist (and it’s emerging, for better or worse). But the political will and informed collective decision making have to exist. There are first order problems around how society is organized that have to be addressed before digital space can be truly liberating. It’s not going to occur in that space by virtue of its existence (short of some as yet materialized deus ex machina sci-fi force). If the last few years have shown us anything about revolutionary change, it’s that real organizing takes place via one-on-one conversations and it has to be connected to political movements in the streets and electoral strategies. More so, if it’s not maintained, it quickly fades. So far, I see none of that happening in this new digital space. maybe I’m wrong, or just a luddite after all. Maybe I’m missing some badass avatar organizer meetups right now (hit me up, y’all). But I can promise that there is nothing truly revolutionary about cryptocurrency and nothing liberating about the meh-taverse, unless you mean the same types of people hoarding the same type of wealth using the same abstruse but populous rhetoric.