What Kshama Sawant’s Victory Means for Organizing and Oligarchy

Kshama’s Recall Campaign leaders celebrating just a little too early last Tuesday

Fiery Socialist Seattle City Council member Kshama Sawant just beat a recall referendum… in a special election… with 53% vote turnout. It’s an unprecedented victory for local socialists and the broader US left, and will likely quell major efforts to unseat Sawant for a while. Her win demonstrates how issue-based organizing can transform even the most crass and unnecessary election into a locus of struggle, and will hopefully inspire left campaigns in the coming years. It also offers insights on the lopsidedness of campaign funding, just how tight polarized local races can get, and how right-wing messaging can delegitimize progressive wins or reframe pyrrhic ruling class victories as the “will of the people.” There are a lot of lessons to be drawn here for future electoral organizing.

A couple years ago, I heard someone refer to Seattle as the epicenter of the American class war. It’s the only place where you have truly outspoken Socialist electeds like Sawant alongside the likes of Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz and dozens of lesser known billionaires. District Three epitomizes this struggle. It covers Schultz’ massive compound and other wealthy enclaves, perennially hip but increasingly overpriced Capitol Hill, and the rapidly gentrifying Central District, which until a few decades ago was Seattle’s only real predominantly Black neighborhood. The area remains somewhat diverse, but now primarily houses the Professional Managerial Class, teachers, Burners, artists and contract workers in the global precariat. I lived in the district for seven years and witnessed these huge economic transitions. Pundits predicted they would be Sawant’s death knell. They were wrong… again.

The failed recall campaign follows mixed results for first-time left candidates nationwide in November’s election, reminding us that taking power is harder than keeping it. There were big wins for Democratic Socialist of America (DSA) members in city races such as Somerville, MA and St. Petersburg, FL. But the political machine trounced us in Buffalo, where DSA member, Nurse and housing activist India Walton beat Byron Brown in the Democratic Primary, only to have elites propel him to victory as write-in candidate in November. Then there are complex results like in Minneapolis, home of George Floyd and epicenter of recent uprisings for racial justice. Open Minneapolis Socialist Robin Wonsley Worlobah won a City Council seat, but a referendum to replace the police with a Department of Community Safety lost with 44% of the vote.

That’s why Sawant’s victory is so important. It helps extend the anti-racist and labor movement moment. It follows Striketober, organizing at Amazon warehouses, and this week’s announcement of a union victory by workers at a Buffalo, NY Starbucks. True to form, the first thing Sawant did in her victory speech was shout out solidarity to the Starbucks union. She is a relentless supporter of organizing (and taxing) Amazon, strikes in general (including a recent controversial Carpenters strike) and -more than anything- the movement for $15 an hour and a right to organize. The success of the Kshama solidarity campaign is a testimony to the power of issue organizing, and to the shitty timing of the undemocratic, barely legal recall campaign that thought a special election in December would do the trick. I’m hopeful that the recall’s failure finds its right place in this narrative of a reinvigorated left.

The special election also offers some insights on the nature of class voting in Seattle and beyond, and the lengths that elites will go through to not only disempower working voters, but to obfuscate campaign finance and manipulate popular conceptions of narrow race results for years to come. While they’re not as exciting as a recall on an intense, at times vitriolic Socialist, there are plenty of local and national votes following this pattern that shine lights on the class dynamics behind campaign spending and spinning. The lefty data dork in me wants to situate Sawant’s “apparent victory” as just the most recent example of why movement work must remain central to electoral work.

Just How Close Was Sawant’s Victory? Did Democracy Prevail?

Pundits will likely make much of how close the election was, how similar the yes and no recall campaigns were, and how much of Sawant’s support came from outside her district. To a degree, they’re right. Sawant barely squeaked by, with less than 300 votes more than the recall as this is being published, out of over 41,000 votes cast, or a whopping 53% turnout. Campaign fundraising and spending was relatively close, too. The recall campaign raised $792,734 while the Kshama Solidarity Campaign raised $984,318, surprisingly outperforming the recall. The recall campaign raised $316,401 from within District Three, or 40% of total donations. Meanwhile, Kshama Solidarity raised $235,565 within the district, or 23.9% of total donations. It was a nail-biter, and at first blush, it looks like Sawant’s votes cost more and were funded by outsiders.

This needs serious unpacking, particularly given the emerging right-wing narrative and how it parallels similar historic ones. 76% of Sawant’s donations came from outside the district, as opposed to only 60% of the recall campaign. There are absolutely “outside agitators” at play here (I should know, I’m one of them). But isn’t the whole point of the Socialist movement… ya know… global solidarity? But 40% of her individual contributors (4,391 people) were in her district, whereas only 33% of anti-contributors (1,683 people) were. She had thousands more in-district contributors. Moreover, the average pro-Sawant District Three contributor gave $53.65, as opposed to $187.94 for the recall campaign. While this is more than Bernie Sanders’ legendary and oft repeated $27, it’s only 29% of what recall donors gave. The campaigns and vote are fundamentally about economic inequality and -ultimately- class struggle.

I guarantee that concentrated, local, working class support is what propelled Sawant to victory yet again, and that the current economic and political moments surrounding inequality, anti-racism, the uprising for Black lives, and police violence against protestors in Capitol Hill drove this support. As did the growing trend towards countless Americans recognizing their positionality under racialized Capitalism. Sure, folks giving $53 probably make a lot more than a Starbucks barista, but many have worked in service, have tens of thousands of dollars in college debt, or are one paycheck, lost gig contract or medical emergency away from eviction or going hungry. They themselves or people they love are harmed by structural racism every day. Sawant has always done a great job of connecting with residents over these very real issues, while centering her political convictions to Socialism. Elevating everyday people and their most important issues obviously works.

A Quick Trip Down Memory Lane

There are several recent votes in Washington (and elsewhere) where elite bankrolling against progressive issues or candidates led to major losses and hobbled movement work. This is also partially because the campaigns didn’t connect enough with working class folks on their issues. But historical revisionism flips this, with the narrative becoming that “the people” democratically expressed their disagreement with such radical ideas and candidates. This is a time-old tradition, but it’s been particularly glaring here. The biggest examples are the 2010 Income Tax Initiative, the 2012 Charter Schools Initiative, and the 2020 carbon tax initiative. They all lost not only due to massive corporate campaigns to kill them, but also a lack of issue-based messaging by the campaigns themselves, and sometimes bipartisan revision as unwinnable here and beyond.

2010’s Washington State Ballot Initiative 1098 for an income tax is the local exemplar of such a fight, and often invoked to justify that fighting to flip our horrifically regressive tax structure is a political third rail. On the surface, this story makes sense. The initiative only received 36% of the vote, an undeniably massive spread. And while it came after the 2008 financial crash, it was before Occupy Wall Street or slogans such as “we are the 99%” entered the popular consciousness. The yes campaign also chose to focus on regressive taxation as a technical and moral issue, rather than creating a fight based on a “who broke it” message or direct confrontation. This likely stems from the fact that some of the campaign’s biggest donors were themselves billionaire philanthropists, such as Nick Hanauer or Bill Gates, Sr.

The yes and no on 1098 campaigns each raised over $6.3 million, with yes outraising no by $50,000. But like with the Sawant recall, you have to get under the hood to see what’s going on. The three largest donors against the income tax campaign were Steve Balmer ($425,000), Jeff Bezos’ parents ($150,000) and the Nordstrom family ($108,000). Seven of the top 10 donors were wealthy individuals, and over half of the top 40 were. They and their firms contributed over $10,000 each, or $2.9 million total. Conversely, the three largest supporters of the initiative were the Service Employees International Union, the National Education Association, and Bill Gates, Sr. Admittedly, they gave over $2.35 million, and they’re followed by a who’s who of guilt-driven plutocrats like Hanauer and Ann Wykoff. But seven of the top 10 and 24 of the top 40 were from unions representing hundreds of thousands of Washington members.

I’m friends with folks involved with the 2010 campaign. They all say the glaring loss set the movement to flip the tax structure back by years. But there’s also a common feeling that running the campaign later with a tweaked message could have had profoundly different results. Extensive polling a few years later by the progressive Washington State Budget and Policy Center supports the idea that people are drawn to messaging centering what’s wrong and how it got that way. They want to channel their issues into action, and not be patronized or offered technocratic fixes. And while there’s no way to know how the campaign would have gone, there is value to knowing where the fights should be.

The 2012 Charter School referendum vote and 2018 carbon tax vote are also telling examples of landslide corporate and elite spending being reframed as a win for Democracy. In 2012, the yes on charter schools campaign raised $11.2 million. In an interesting twist, this was primarily directly from elites such as Gates, Balmer, Hanauer, Bezos and others who had two years ago been deeply divided and given much less. The no campaign raised a measly $725,000, largely because the yes campaign raised so much, so early, that everyone expected it would absolutely crush. Even the Washington Education Association took it as given. But Charter Schools only won by less than 1.4%. So the yes campaign outspent the no campaign by over 15 to one and barely squeaked by. A modicum of organizing and fundraising could have beat it. Campaign financing isn’t everything.

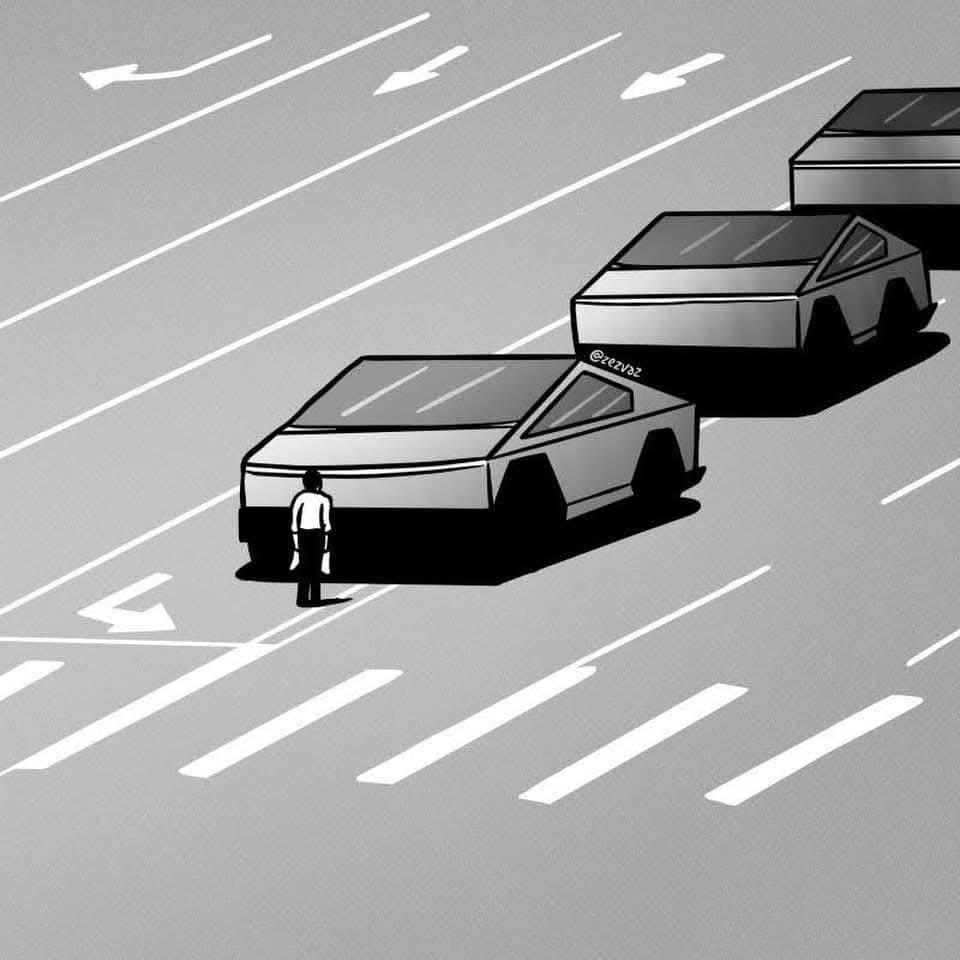

By 2018’s Initiative 1631 for a carbon tax, the progressive flank was running more aggressive, adroit campaigns, and included the broadest coalition of labor, environmental, religious and welfare groups I’ve ever seen (with the exception of a handful of building trades and oil industry unions). I volunteered on the campaign and was impressed by the messaging, which was oriented around connecting with working people on their issues and holding corporate polluters to blame. They raised an impressive $16 million from people of all backgrounds. But the no campaign -ran by the “Western States Petroleum Association”- raised over $32 million. The largest donors were BP ($12.8 million), and Phillips 66 ($7.2 million). Two global corporations gave two-thirds of the funding, and more than the entire yes campaign. It was so lopsided that the biggest individual donor was a guy named Joe, at $500. They spent double the yes campaign, but won with only 56.6%. This means they spent almost $18 per vote. Pyrrhic indeed.

By now, you’re probably saying something like “why are you listing all these initiatives and throwing annoying numbers around when all we want to do is celebrate Kshama, bro?” I realize this is weedsy and that there isn’t a one-to-one between candidates and initiatives. But I think it’s important to highlight the nature of class dynamics, messaging and issue organizing in local and statewide campaigns, learn from past mistakes, and have more in our arsenals when confronting reactionary revisionism. Did the Seattle Times rail against the state’s richest billionaires for not wanting to pay their fair share or privatize public education, or against the interlopers at “Western State Petroleum Association” like they have with working class people from around the country defending a Socialist? Of course not. They never will. It’s not in their interest. Just like it wasn’t in the interest of the California press to highlight how Uber and Lyft spent $250 million last year convincing voters that drivers were “contractors” rather than employees, then win with 56% of the vote.

All of this is a reminder of how important it is for social movement candidates to win and retain electoral office. It’s a well-established fact that it’s much harder to get into office than it is to be voted out, even for firebrands like Sawant. When movement candidates combine political adroitness, issue organizing, and accountability to their electorate, they can beat the corporate floodgates. They can also elevate the crucial issues. We just saw this nationally in Bernie Sanders politicization of the budget reconciliation process or “Squad” members obstructing terrible infrastructure compromises. If we have more smart, savvy, strategic movement electeds, then we’ll also go much further with passing legislation or running people-powered initiative campaigns. Indeed, if we want to win the biggest transformations, such as Medicare For All, a Green New Deal, or voting rights, then we have to win and keep office. If we want to do that, we have to run and win organizing campaigns, and build organizations (such as DSA) to sustain them.

If the last few years are any indicator, then the left is finally on the “right” track. For the most part, Sectarian infighting seems to be diminishing. Genuine anti-racism and class consciousness are fusing. Acceptance of multiple electoral pathways seems to be beating out stale arguments about the Democratic Party. The importance of people-powered, issue-based organizing is triumphant. My close friends and comrades know that I have numerous strategic disagreements with Sawant and her organization, Socialist Alternative, and I’m often among the first to critique her style. But I’m ultimately overjoyed today and all others to call her my comrade, to share in the struggle with people like her, and to channel energy into the organizing and issue campaigns that will get more of us into office and transform society.

Solidarity forever.